Pages of A Humument: Tom Phillips On His Show At Flowers Gallery by Vida Weisblum

This article appeared in ArtNews, August 6th 2015

On a recent Saturday evening, the 78-year-old artist Tom Phillips was casually perched on a stoop on West 20th Street in Chelsea. He was instantly recognizable from several yards away by his burly beard.“I didn’t choose a very good hiding place,” he said wryly after a reporter greeted him, before leading the way to Flowers Gallery, on the third floor of a neighboring building. On view there are 100 prints of pages from the newest version of A Humument, a project to which he has devoted the past half-century of his creative life.

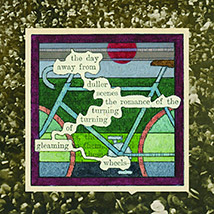

A Humument is a work of interwoven literary and artistic genius. It began with a trip to a thrift store in 1966, where Phillips gave himself the task of finding a second-hand book to work with. His plan was to alter each page with collages and drawings, carefully cherry-picking a handful of words to leave unobscured so as to make poetry out of the existing text.

Phillips chose W.H. Mallock’s 1892 Victorian novel A Human Document, produced from a collection of diaries, letters and notes, as his working material. The book’s stark yellow cover popped out to him at the store, Austin’s Furniture Repository, in London’s Peckham Rye neighborhood, where, Phillips once wrote, “William Blake saw his first angels and van Gogh must have passed once or twice.”

Ever since finding his canvas for A Humument, Phillips has devoted his life to working his way through the book’s 367 pages of text, creating news works out of each page. A Human Document has a vague plot. It is imbued with Mallock’s apparent bigotry and snobbery and includes characters with names like Eve Sardine and Ted Wink. (In 2012, the London Review of Books said that Phillips’s book is a “teeming world of humour, sex, sadness and art that would have baffled and shocked the conservative Mallock.”) “It was a wonderful book to work with,” Phillips said. “So much so that I’ve read a lot of other books since and thought, ‘What a bit of luck.’” Mallock, he said, gave him “a lot to argue with and a lot to agree with.” The new title he gave to it, Humument, which is a made-up word, has acquired meaning over time, he said. “There are little echoes within. It’s a funny little word. Human and humument and exhumed, earth humus, and all that. That pleases me because it’s not fixed.”

The show at Flowers is modeled after a massive exhibition of Phillips’s art, titled “Life’s Work,” which took place at MASS MoCA in 2013 and included the most comprehensive exhibition of A Humument ever mounted. At Flowers prints of three versions of 100 pages—the original page, the first version Phillips made, and the newest version—are hung in three parallel lines throughout two rooms so that they can be compared. (“It’s very tidy when it comes on to the walls,” he said. “It’s not tidy where I’m working, it’s all over the floor.”) One room also contains pages from the opera libretto that Phillips created using the same pages from A Human Document.

Phillips published a complete first draft of A Humument in 1973, and has continued to alter it, 50 pages at a time, since then, publishing new sets as he goes. He has currently completed five new sets, and will finish the second full version of the book by next year, when it turns 50 years old. “With the first version I thought, ‘Hey, this is fun to do…so I did it quite quickly,” Phillips said, “and then kept thinking, ‘There’s more to this than I supposed, more that you can get out of this material than I first thought', so I thought, ‘Well, let’s have another go!’ Bit by bit, I went through all of it again.” The second version includes a wider range of techniques and media. “I just didn’t know what the possibilities were at the beginning,” he said.

Phillips's carefully composed poetry lends itself to an abundance of readings. Page 159 of the second version, one of the less visually cohesive of the book, seems to contain a loose signature in a white box (perhaps his own) and the following poem: “Whilst I/now/slowly watch white drops of dream/come laden with/life/unfolding/ to read the/sign I write the dreaming––dream-/fragments of poetry/-fragments of/my mind;/its petals/unfolding.”

Phillips focused on English at Oxford, but also took drawing classes and lessons on Renaissance iconography, and he later studied under the artist Frank Auerbach at the Camberwell School of Art. Perhaps thanks to that diverse array of study, A Humument is hard to fit into any existing categories of works, whether artistic or literary. It has both the sui generis obsessiveness of folk art, the intensely sophisticated craftmanship of medieval illuminated manuscripts, and a solid dose of 20th-century avant-gardism. “It didn’t have a genre at all,” Phillips said. “So I called it a treated novel.”

Quite a few poets and artists have followed Phillips's lead, including Austin Kleon, who is known for blackout poetry, which is created by covering newsprint in black marker, though Phillips believes that his strength in drawing is what tops the work of followers. “I do think [drawing] is very important,” he said. “That’s the difference. It’s a book by an artist, not an art by a bookist.” Phillips has done translation into verse, but has not done much original writing without using pre-existing text. “I suppose I’m a trained writer in a way because I did English at Oxford, but mostly that was training in drinking,” he said.

Phillips said that poetry is always in the back of his mind while he is working, and choosing a selection of words is his first step in creating a page. Much like a poetry collection, each page is intended to be read in dialogue with the others, but not necessarily in its suggested order. “There are as many echoes of other poets as there are of other artists [in the book],” he said.

Phillips worked in a random order, first picking out interesting phrases and words from certain pages that he thought might relate to one another, then adding the drawing, painting, and collage to accompany the poems. Although there is no clear narrative, little stories occur throughout the book, with a couple of characters floating in and out at random. The most prominent of these characters is named Bill Toge, whose first name comes directly from the word “bill” and last name is formed from the words “altogether” and “together” (a nod to Phillips’s unique collaboration with Mallock). “That becomes a little rule,” Phillips said. “The book has little rules … I found the guy on the page and he came with the word ‘bill’ … which sounds like Mister Bloke to me, Mister Ordinary Chap.”

According to Phillips, Toge is a sad character, but becomes more cheerful toward the end. “I thought I was giving him too rough a ride,” Phillips said, adding that he infused humor within A Humument because he didn’t want to make “a dull book.” Pages of the book are filled with a variety of sentiments. Some pages are romantic and idealistic—painted with red roses, rainbows, and hearts—while others are sexual and sarcastic, with a biting, dry sense of humor.

Various references to popular culture and political characters or ideology conjure these emotions and moods. For instance, page 266 of the second version, a hodgepodge of colorful crosshatched comicstrip images featuring a blonde woman with a tear on her cheek, reads: “remember/ bush/ bush/ remember that bitter name/ remember him. The rude stare at destiny.” Phillips mentioned that his use of these cultural and political references have evolved over time, and sometimes newer references have a way of relating to older ones, for instance texting or Facebook. “As the language has changed, the opportunities have changed,” he said.

The visuals for the first version of Phillips’s opera, IRMA, named after the “two-timing woman” and heroine in A Humument are also on view. IRMA, for which he wrote the libretto and score in 1969, contains some of the same characters and references—no surprise since he developed it from the same text; some of the pages of A Humument reference the opera as well. Having originally bought A Human Document for threepence, Phillips has declared IRMA a three-penny opera. The piece has been performed twice and recorded, and Phillips has created a second full version of it.

Phillips has also created small works using square-shaped blocks of text from A Human Document, which he sometimes uses as birthday cards. Despite their diminutive size, they are impressive. His rule about scrap material: “Don’t throw it away!”

One of his many upcoming projects stems from even smaller fragments—the “bits,” as he calls them, that are left over from collages of pages past. The project will be a tribute to his years working on A Humument and to Mallock for his tremendous contribution, of which he is, of course, unaware. (He died in 1923.) “I have a use for [the bits],” Phillips said.

He is also in the midst of other projects, which extend beyond A Humument. “I work all the time,” Phillips told me. At the moment he is painting a chapel in a cathedral in London. The painting isn’t a “religious thing,” according to Phillips, but a “visual thing.”

As for the future of A Humument, Phillips believes that once he finishes the complete second version—he is down to the last couple of pages—it will be done. “Fifty years is long enough to work on the piece,” he said. “It’s got it’s shape now, and it’s got its shape in time.”