Fifty Years to Make : Tom Phillips interviewed by Harriet Fitch Little

This article originally appeared in The Financial Times, 19 May 2017, with the title, Artist Tom Phillips on the masterpiece that took 50 years to make.

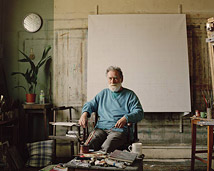

If Tom Phillips were not an artist he would be called a hoarder. In the kitchen of his south London home there are files containing close to 50,000 postcards. In the studio he stores pots of mud from everywhere he's visited – Peckham mud filed next to Princeton mud, and so on – and mason jars stuffed with beard trimmings dating back decades. Phillips has used a pole to draw huge charcoal faces on the ceiling and this, combined with the yellowing, scribbled-on walls, gives the room the cocooning effect of a cave. "You can see it's chaos, can't you?" he says cheerfully. Chaos, perhaps, but in the sense in which a scientist might use the term: the disorder of Phillips' studio masks deeper patterns of order and interdependence. He is a painter, a poet, a composer (in the 1960s, Phillips was a founding member of the experimental Scratch Orchestra) and a sought-after portrait artist. He works with collage, cut-ups and bricolage – most projects cut across several categories. "Sometimes it turns out I was right and, yes, these things do all join together, and sometimes they don't and then it looks like muddle," he explains. He is on the mark more often than not, however unpromising certain collections might seem at first glance. I recognise the beard trimmings from the ingenious sculpture "The Artist Encounters His Younger Self" (1997) – two hair-covered skulls, one black, one white, presented as a reflection on ageing. This Friday, the day after Phillips' 80th birthday, a retrospective opens at Flowers Gallery in east London. Called, fittingly, Connected Works, the exhibition will offer new insights into one of Britain's most eclectic artists.

Born in 1937, Phillips studied English at Oxford university, taking life-drawing classes at the Ruskin School of Art on the side, then spent his twenties in a succession of teaching positions. In 1966 he began the project that would become his capstone work. Browsing a second-hand shop in Peckham, he selected a cheap Victorian novel at random and set about altering it, page by page. By painting over the majority of WH Mallock's obscure romance A Human Document (1892) he created "A Humument", an entirely new work of poetry, collage and – as William Burroughs once called it – "a funny sort of science fiction". Phillips reworked this same text obsessively for exactly 50 years, publishing it in its sixth and final edition in November last year. "I've never thought of anything or had anything to say that I couldn't find in that book," he says. He believes, and not in a glib way, that the text has powers of divination: "You lean on it, then you find it gives you something back." I decide to test this theory, opening the book at random on page 106. There's an illustration of a dragon, and the words left visible do indeed roll off the tongue like a drunken devotional: "Bound to a frown of pounds at my bank o great officials carry me back to my fine fortunes help me o money men." Money worries, I think. How apt. But when I read the prophecy to Phillips, he has his own interpretation. "Well, it's the Financial Times – you've come to see me," he says with a singsong joy. "You couldn't have been better on the mark." So "A Humument" has passed the test of all good oracles: it is an inkblot on to which we project our concerns. Phillips says that finishing "A Humument" felt like a bereavement: "I'm a lost soul without it now." Then he rephrases the sentiment more poetically: "A lost soul facing a black hole."

This is a bleak proposition. Thankfully, it is not entirely accurate. Phillips may have finished "A Humument" in book form but he continues to fold it into other parts of his practice. The retrospective at Flowers will include "Humument Desk" (2016), a school desk covered in fragments of the text. He has also used it to score the experimental opera Irma, which, after decades of development, will have its full-length debut at the south London gallery this September. "I hope I haven't finished anything really," he says. In fact, there's only one project Phillips can think of that he has consciously abandoned: "I sort of don't do portraiture any more." Perversely, this is the only venture that's ever made him any real money. In the 1980s, Phillips' sitters included Samuel Beckett, Iris Murdoch and his one-time student Brian Eno. He was the second living artist to have a solo exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London. "But it became too much a way of earning a living," he explains. "I got asked more and more by people I wanted to paint less and less."

There is a supreme confidence to the way Phillips works, persevering with his grab bag of projects unperturbed by the knowledge that most critics think, as he puts it, "there are too many things". ("That's usually true, but if it's what I wanted to do then how can I complain?" he asks serenely.) When I push him further on the "why" of it all, we end up at Wittgenstein, whose theory of ethics and aesthetics being one and the same has, Phillips says, been a major influence. But analytic philosophy is a bridge too far for a sunny May morning – "very pretentious", Phillips agrees – and we quickly retreat to less abstract ground. Suffice to say that Phillips' approach is uncommonly holistic, perhaps even fatalistic. He pursues his collections simply because they interest him, confident their artistic value will reveal itself with time. The 50,000 postcards are a case in point. He has filed them according to theme – "Women in Uniform", "Men at Work", "Enigma" – because he has a hunch that these images contain the same unintentional universality that he found in Mallock's A Human Document. "That must be the thing that drove me to amass them in the first place," he says. But he has yet to find the format that will release their potential. "It might beckon from a different direction or another corner of the room saying, ‘But you could do this…’," he says. "It's that voice I'm waiting to hear."

For now, a temporary distraction: Phillips is a Man Booker Prize judge, and currently working his way through this year's potential longlist of novels. In the kitchen, where he retreats for a cigarette break mid-interview, his 100th book is propped up on the table. An Akan gold weight is positioned so as to hold its pages open. Prompted by a question from our photographer, Phillips explains that he is also the leading authority on these Ghanaian brass statues, and has a collection of several hundred. He has illustrated a book on them, and curated the Royal Academy's exhibition Africa: The Art of a Continent (1995) and, and … the list continues, the web of connections grows.

"You know that lovely line of Beckett – ‘I can't go on, I'll go on' – that's how it feels," he later tells me. This is the last fragment of Beckett's disjointed, plotless novel The Unnamable. For one of the more recent works in his retrospective, Phillips has stencilled the lines on to a paint palette – a homage to the relentless, contradictory impulses of the creative mind. "I get frustrated if I don't use the ammunition that's given me and the armoury that I have," he says. "That at least I used it all up, or tried to, that's all I can claim."