We are the People: Return to Sender by Matthew Sweet

This essay originally appeared in The Independent, 22 February 2004, with the title, Return To Sender.

As any deltiologist worth his stamps will tell you, the modern photographic picture postcard entered the world a few months after it was vacated by Queen Victoria.

In 1902, the Royal Mail pronounced itself happy with the idea of carrying cards that bore both the address and a message on one side, leaving the reverse free to carry a picture of anything that the sender liked: a scenic view of Flamborough Head; a portrait of Lillie Langtry; a smutty cartoon. Or, perhaps, a photo of the person who scrawled the message and licked the stamp, sailing up above the clouds in an unlikely-looking cardboard aircraft, or holding his daughter for one last time before going off to eat rats in the trenches.

With this tweak to the postal legislation, photographers - of the studio, street and beach variety - found their businesses invigorated by a new, cheap and accessible form of self-representation. If the family was having a good time in Scarborough, they could prove it with photographic evidence. If one of their number wanted to dress up for a lark as Kaiser Wilhelm or a rabbit or a road sign, then the postcard photographer could oblige. If they wanted to see themselves driving about in a car they didn't own, or floating through the sky in a balloon, or bombing Dresden in a Spitfire, then that, with scenery and props or a double-exposure, was also possible. The result was a democratisation of photography: thousands of ordinary people sitting in front of a camera for the first time in their lives. A nation saying "cheese" together.

Tom Phillips, the artist best known, perhaps, for his much reproduced portrait of Iris Murdoch, a Titian and a ginkgo plant, has made a lifetime's study of these images. His collection of 50,000 cards has already formed the basis of a book, The Postcard Century, which used the messages borne on their backs to retell the history of the 20th century. He has sorted through again to furnish the exhibits for a show at the National Portrait Gallery entitled We Are the People. It will, he suggests, be the first time that the gallery has offered a true portrait of the nation - rather than just a sample of its most celebrated members.

"They're a vernacular photography," he explains, poring over the exhibition catalogue, "when photography seemed able to do without a fanciful aesthetic, without an idea of glory. It was just an instrument for looking at things. There 's no artistic idea in these photos, and yet there's a great artistic presence." The postcard photographers, he argues, were taking Diane Arbus shots years before Arbus bought her first bottle of developing fluid. "But she had to build a whole aesthetic to justify the same kind of confrontation between photographer and subject. These have it without any baggage."

A residuum of such practices, however, survives. The school photograph retains the presentational plainness of many picture-postcard portraits. Street photography persists - just - in seaside resorts: there's a man on the seafront at Blackpool who invites punters to let him shoot them entwined with his pet snake; there's a man on the beach at Cannes who bullies passers-by into having their picture taken while being hugged by a colleague in a greasy Bugs Bunny costume.

Phillips's postcard images of early-20th-century punters in fantastic modes of transport have their antecedents in the shot of your screaming family that's taken as you plunge over the log flume at Alton Towers, and the set-up at the Brighton Aquarium which allows you to sit in a fake rowing-boat and incorporate yourself into a codded-up image of a shark attack. I have a friend who, throughout his college years, carried a snapshot in his wallet that depicted him arm in arm with Patrick Swayze - a novelty harvested from an Australian amusement arcade, and more convincing than it had any right to be.

Eventually, such images may find their way to tomorrow's flea-markets and ephemera fairs, where they will be as anonymous as the figures massed on the walls of the National Portrait Gallery for Phillips's show. A couple of subjects in We Are the People, however, will buck this rule. Phillips has included two pictures of his own parents. His father appears in a shot from the first days of the last century, taken during his time as an amateur boxer. He is stripped to the waist, both fists raised as if to hook some unseen opponent. His mother is depicted in a portrait from the 1930s, buried in a fur wrap and standing beside an elaborate carved chair, upon which sits a placid dog. If Phillips had plucked these figures from some shoe-box at a postcard fair, they would have been filed under Sport and Dogs respectively.

He tells me the story behind the pictures. His father, a businessman, divorced his wife to marry a member of his secretarial staff, and then went bankrupt just as his son was born. "There were terrible ructions," Phillips says, darkly. "He was a smart businessman but I'm not sure everything he did was entirely kosher." As he describes their lives, I am reminded of the plot of Stanley Houghton's play Hindle Wakes, in which a mill girl's affair with the boss's son is exposed when her friend fails to send a decoy postcard from Blackpool to her mother and father.

Any one of the cards in Phillips's collection might yield such a story. The more you gaze upon them, the more they seem to invite you to use them as raw material in the construction of some family narrative. Were the people who lived next door to the butcher's shop happy about having pig carcasses draped over their garden fence? Did this husband always demand that his wife surrender her garden deckchair to the dog? And the boy dressed as a bunny - did he drown, was he shot, did he expire quietly in his bed, or is he sitting in a nursing home in Lancaster, staring at these pages in disbelief?

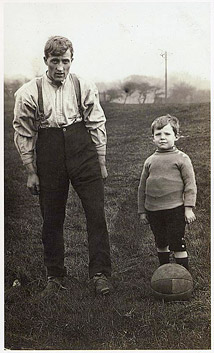

This is the pleasure and the hazard of these images: they offer a glimpse into the lives of the dead; how they arranged their hair, how they buttoned their collars, how they smiled or didn't smile, on an afternoon now lost in time. But they also allow us to pursue our fantasies about what the past was like. These two men lolling together in the grass; the women smiling from the steps at the beach - are they lovers, siblings, friends? What did it mean to put your hand on someone's shoulder in 1906? Do these photos record the secret desires of their subjects - or do they measure our own squeamishness about those with whom we consider it appropriate to hold hands in front of camera?

"Their identities are so fresh," marvels Phillips. "Concealment doesn't seem to be part of the game. As the camera isn't artful, the people aren't being artful. People who palpably don't look very good, have just gone along to have it done; like getting a tooth removed. They present themselves because they want to represent themselves. They do it convincingly."

He points out an image of a bearded middle-aged man and a girl of about seven. They are sitting side by side in front of a painted backdrop which suggests the drawing-room of a country manor: thick curtains, broad leaded windows, the silhouette of an urn. The man is in three-quarter-profile; the girl, in a neat dress and white kneesocks, fixes her gaze upon the viewer.

"A photo like this would never occur now," reflects Phillips. "This man and that girl have gone to a studio. They've sat in this way. There's no problem. Look how relaxed their hands are. They have a fantastic frankness. There's no equivocation in these pictures. They are conscious and confident that their existence is worth recording. Here I am', they're saying. Here I am.'"

See We Are the People in The Trade Publications section.