Humbert by Simon Callow

Humbert is A Humument’s second cousin twice removed. I was delighted to make the acquaintance of this relative, having long been a devotee of the original, in all of its evolutions. I came across a copy of its first iteration in a second-hand bookshop in the West Country, much as its author came across W H Mallock’s A Human Document, of which A Humument is a transfigured version.

My eye was initially drawn to the book because I had no idea how to pronounce the title. I found that out pretty quickly, then settled down to read it, but immediately realised that, approached linearly, it made Finnegans Wake seem like Enid Blyton. Any attempt to trace a straight line through it was absurd.

What struck me even more strongly than its complexity and multiplicity of techniques was a contradiction: Phillips’s separation of individual words from Mallock’s text had an oneiric feel to it, as if the words had autonomously drifted together to make new meanings, but the page upon which the newly created sentence appeared was worked with a fanatical, obsessive intensity, often in minuscule detail, uniting rhapsody with hard graft. Its weightlessness was framed with painstakingly wrought meaning and purpose.

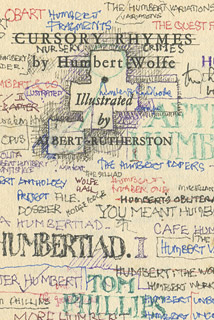

In Humbert there is this same tension, but, as Phillips observes, the scope is both wider and looser. Humbert Wolfe’s whimsical, sometimes reach-me-down, verses, from his 1927 collection Cursory Rhymes, have less resonance in themselves, even fragmented and re- arranged, than Mallock’s texts, but the context is more variegated, sometimes seeming to have no connection with Wolfe’s reshuffled words, sometimes reflecting them.

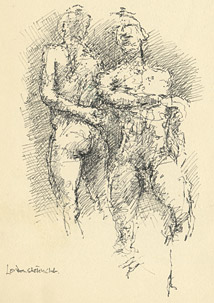

Phillips admits that Humbert functions, at times, as a commonplace book, a collection of significant ephemera, and a record of his then current preoccupations. He moves from page to page as the impulse takes him, producing now a collage, now an intensely-wrought abstract painting; found objects adhere to the page, which set off punning associations – a salmon rösti label summons up Salman Rushdie. Here a self-portrait, there African shapes which remind us of his curation of the great RA exhibition; now exquisitely spectral life studies, now a matchbox.

Doodling with intent, he says on one page, and it is as good a summary of his method as any. Meanwhile the pages themselves are framed with cubes of writing in his exquisitely unreadable hand – notes to self, epitaphs, practical observations – which add another dimension of mystery and possible meaning: it might as well be in Cuneiform.

The book is thus an enigma and a ravishment, filled with visual and verbal echoes of echoes. As such it is a perfect vademecum, a travelling companion to be pulled out on a train journey or to be pored over in the small hours of the morning with a tot or two of Drambuie. There really is nothing else like it that I know of.