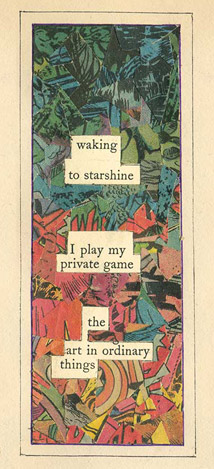

The art in ordinary things (a private game) by David Jennings

‘No one plays – no explorers – no more dreams.’ These words on an early page of Humbert appear next to a note about the lack of a Wimbledon tennis tournament in 2020’s lockdown; but they could also be read as a mournful commentary on innovation in bookcraft. Where is the Laurence Sterne of the 21st century? Humbert – playful, exploratory, liberally seasoned with dreams – announces itself as a contender in that arena. And like Sterne, it teasingly navigates the line, more as poacher than as gamekeeper, between sense and nonsense.

If you root around on Tom Phillips’ website, you will find reference to a ‘now abandoned’ multivolume project, Humbert’s Obliterated Rhymes, that ‘developed from tentative beginnings in the seventies. Phillips (henceforward TP) is perhaps best known for his other treated book, A Humument, which he worked on from 1966 until its sixth and final edition fifty years later. With Humument ‘now closed, I guess’, writes TP, uncertainly, in this new volume, he clearly isn’t finished yet with messing about in books. This, together with the exigencies of lockdown, must have prompted TP to take down from the shelf his collection of Humbert Wolfe’s Cursory Rhymes. The version that results is, he explains, a compilation of selections from the original volumes with additions and reworkings from 2020 and 2021.

What then does Humbert comprise? There is no index or table of contents, no clear sequence or themes. We readers must compile our own inventory from the fragments that we find scattered through the pages. Here is mine, in brief.

1 – Abstract shapes and patterns that divide the page in a variety of ways – my guess, from their similarity to early editions of A Humument, is that these are among the oldest elements.

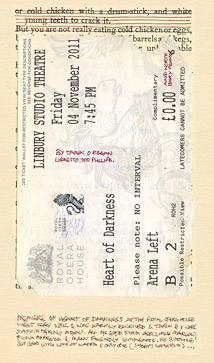

2 – Diary notes and journals, dated across the last 30 years, covering projects, shows, Royal Academy work, visits the opera with his wife and others, the premiere of the Heart of Darkness opera for which TP wrote the libretto (‘no boos’, he notes), and visits to the Oval (one page, decorated with ‘Lara’ and ‘70’, records the score that TP witnessed the great batsman making just the day after his record 501 in 1994).

3 – Memorabilia and ephemera: copies of access passes to the Guggenheim Museum and the BBC (with a disgruntled memoir of wasting time discussing a poor translation of Dante on Night Waves), tickets to see Placido Domingo at the Met (a brief encounter with Jack Nicholson there), and to see his daughter’s cello concert. Though even the most quotiden of found objects – such as a torn section of food packaging – may later be revealed to signify and connect.

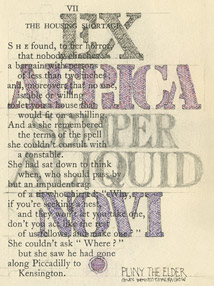

4 – Notes and sketches related to TP’s many projects. These include his annual walks round London’s SE15, SE5 and SE22 postcodes for 20 Sites n Years; trips to Africa, sketches of African goldweights, and reflections on African Art (he draws Pliny the Elder’s line, ‘Ex Africa semper aliquid novi’); Mallarmé’s dice; the black and white tennis balls he created using his own hair; Merry Meetings (his sketches in the margins of Royal Academy committee papers, perhaps the closest sibling to Humbert among TP’s works); his recent illustrations for an edition of Tristram Shandy; and for a forthcoming edition of T.S. Eliot’s Wasteland.

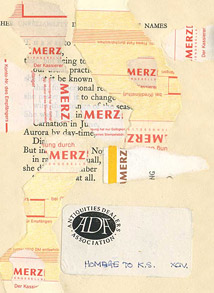

5 – Homages to other artists: Kurt Schwitters, M.C. Escher, Nestor Redondo, the Filipino comics artist, best known for his work on TP’s beloved DC Comics, whose influence adorns many other pages of Humbert.

6 – Life drawings from the London Sketch Club. As an artist, TP says in his introduction, one always remains a student.

7 – Fragments and examples of the ‘rivers of type’ concrete poetry that are a staple of A Humument. TP explains that he initially ignored Humbert Wolfe’s rhymes and prized the book instead for its wide margins. Some treated text is imported from elsewhere including A Humument’s original wellspring, A Human Document. The results are as unpredictable as ever, ranging from astrophysics (‘Dark matter, matters – a night song’) to a riposte to Bob Dylan (‘Who knows, babe – it might be you’).

8 – Commentary and essay that I imagine may have been inserted after the Humbert project was revived and reframed during lockdown. TP eagerly follows the progress of the French tennis player, Ugo Humbert, as the tournaments begin again. On a page titled ‘Humbert v Humbert Humbert’, he pastes his own (unused) cover for Nabokov’s Lolita on top of Humbert Wolfe’s poem. There’s an essay – apparently from 2005 and incomplete – on the elements of dreams: parents, sexual encounters and taboos, criminality. And the first part of a Slade Lecture on Seven Types of Realism, more of which in a moment.

9 – Accounts of TP’s own dreams, mostly dated between the early nineties and 2021. One of the most recent is of a ‘series of prints using experimental inks that made lovely cloud colour and mystery shapes.’ TP is disconsolate when, on waking, he cannot realise this vision. Another from 2013 is part dream, part trance, involving lung surgery, men with pills and a ‘ghastly green light with a spot of darker green, like a… compressed graphic score from which I hallucinated other scores which are almost entirely black.’

10 – A series of collages and patterned abstracts that, from their style and the use of some of them in the Tristram Shandy illustrations, I take to be from more recent years.

You will of course find pages that do not fit this uneasy taxonomy, and others that combine or transcend the categories.

‘I play my private game – the art in ordinary things’ reads a river of type in another early page. TP curates for us ordinary things from his work and life. Many are private concerns in TP’s internal life and do not yield their signification lightly. While readers within reach of South London can still find some of the sites he mentions, the Peckham cafés whose life TP catalogues are long gone. Readers familiar with the names of TP’s children, assistants and patrons will have a different experience of the notes that mention these people, compared with other readers who are not. We are all teased to speculate what made Jill Sackler, at a do for the American Friends of the Royal Academy, ‘better company than most.’ And why, when TP’s tally of votes for the president of the RA shows that Sir Philip Dowson is elected, is there an ‘UGH’ next to his name? This playful approach to privacy – a very contemporary concern – shows how, to transcend Wittgenstein’s Private Language argument, there can be a private game if readers are willing to take on the role of players.

One possible precedent for the diary elements of Humbert might be A Year with Swollen Appendices by TP’s former student, Brian Eno. (Eno himself appears in Humbert in the context of a dream, undated, involving TP’s African goldweights collection, the Horniman Museum and a mortgage!) Both books lift the veil on some of the false starts and dead ends of creating art. Normally we see only the works – as in the case of Humbert itself – after they have been exhumed and rehabilitated from any abandonment. But the book includes a few sweepings from the cutting room floor, including TP’s tantalising sketch for a proposed Folio Society illustrated edition of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. The curt note concludes, ‘but Mrs Calvino forbids.’ Perhaps more painfully, a cinema exhibition programme for A TV Dante (TP’s 1980s collaboration with Peter Greenaway), is annotated with a comment that he was forced to ‘step away’ from the project, and that the then-planned involvement of Terry Gilliam and others never transpired. Another note records how much time it takes TP to pack up his voluminous postcard collection to send to the Bodleian Library, and ‘what to do with the surplus thousands’?

‘How might this book be read?’ asks TP at the end of his introduction. It’s a question that readers will find themselves confronted with repeatedly as they unravel the chains of connection within the book, beyond to TP’s other work, to our ever-morphing culture and to our experience of the world. ‘It’s like a labyrinth of loose ends which mostly turn into cul-de-sacs’, TP answers his own question. Sometimes, too, the loose ends knot in circles, as when TP’s Lolita book cover includes, via a review of Stanley Kubrick’s film of the book, a quote about Humbert Humbert speaking ‘in a voice both randy and devotional, as if Dante were singing an ode to Beatrice in her first bikini,’ and thus back to TP’s illustrated translation of Dante’s Inferno.

It has been said of Tristram Shandy that, ‘pointlessness was one of Sterne’s points… he was out to flout and taunt humdrum expectations.’ I think the point of Humbert’s loose ends, cul-de-sacs and knots is more than just épater la bourgeoisie: its pointlessness is a playful conjecture about the nature of reality and meaning. In the fragment of the Slade Lecture on realism, TP writes, "Perhaps we should look for realism when we have decided what reality is: everything that is the case [Wittgenstein again] etc or in our internal lives. The bits we do not daily represent. What we mute and hide. And this is precisely the job that opera takes on".

I know too little about opera to grasp that final sentence. I wonder though if this is not also the job that Humbert takes on. The way that reading Humbert requires effort. TP’s miniscule and sometimes ‘wireframed’ handwriting operates on both sides of the threshold of legibility. Connections emerge, crystallise and dissolve away again. Going back 50 years, TP’s experiments with stencils explore the point where letters emerge out of abstract forms, shimmering on the edge of indecipherability and formlessness. As if by taking writing to its extremes we can recover the point where it merges again, in some prelapsarian Eden, with music and the other arts.

TP is now 85. His notes include tributes to departed and departing friends: the poet Christoper Logue (‘one of the first people who ever bought a work of mine’); Marvin Sackner, a longstanding patron and collector; and a note on Easter Sunday 2021 that Harrison Birtwistle is seriously unwell with a touching coda about the manuscript of the piece that Birtwistle wrote for TP’s 60th birthday.

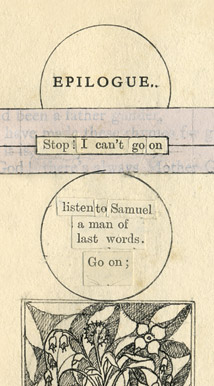

On the same day, TP is starting a new oil painting – tentatively – after much time spent pastelling, collaging and messing about in books. Humbert collects examples of each of these, together with projects in many other fields, a changing visual style, a slow defection from cricket to tennis. The connection they all share is TP himself. ‘Stop,’ he writes in the first of two Epilogue pages, ‘I can’t go on'. Then: 'listen to Samuel [Beckett] a man of last words. Go on;’ And so he does.