Optical Magic: Hockney Review

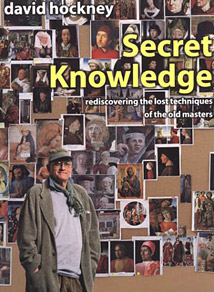

A review of David Hockney's book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. Originally published in the Times Literary Supplement, 2 Nov. 2001, p. 12. Reproduced with permission.

Do artists cheat? A bus ticket was the nearest we got to it in my art school days. The secret from the Euston Road was that London Transport tickets (which strangely came in all sorts of Sickertian mauves and Ginneresque greens) had neat divisions along their sides. These, at arm's length, served to measure key proportions of the model, eyes to mouth, nipple to navel etc. It was considered an advance on the traditional squint at a raised pencil. How the good news was brought from Camden to Camberwell I do not know but I had it from Euan Uglow who had it from William Coldstream, a fragment of esoteric studio lore as yet unrecorded by art historians.

Can artists cheat? That is a deeper question at the heart of David Hockney's pictorial detective story. His book is subtitled 'Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters' to whom he ascribes grander methods of self help involving much juggling with lenses and mirrors and darkened rooms. He extends his list of optically assisted practitioners way beyond the usual suspects like Vermeer and Canaletto to encompass virtually the entire pantheon of painting. He is however at pains to point out that such techniques were not responsible for the quality of the work; "optics do not make marks, only the artist's hand can do that and optics don't make drawing any easier either."

The first report of Hockney's investigations appeared in the RA Magazine (1999). Marvelling at the Ingres portrait drawings in the National Gallery exhibition he spotted anomalies. The small scale surprised him as well as the frequent disparity of proportion between meticulously observed head and the shorthand of clothed bodies. The young Ingres made ends meet as a jobbing portrait draughtsman in Rome, making studies of whatever Milord or Comtesse Quelquechose could be enticed into his studio. Wealthy or noble nonentities, as their Grand Tour souvenir, would unwittingly be immortalised in a portrait by the greatest draughtsman of the age.

Hockney suggests that Ingres used a camera lucida (a prism on a stick that causes the scene in front of the artist to be projected on to his sheet of paper) for the initial blocking of features, refocusing to capture the outlines of the costume. I suspect that to an artist of Ingres' fluency (and rigorous training) such an operation with its problems of movement and parallax would be an encumbrance.

This speculation made Hockney try out the apparatus himself by drawing the National Gallery's wardens. These look pedestrian besides the artist's more familiar drawings which are characterised by a delicacy of nuance and an economical conjuring of volume rarely equalled in our time. The new certainties are no substitute for the old intuitions.

Like Sherlock Holmes embarking on a case Hockney was restlessly sniffing at larger questions. He soon found himself an admirable Dr Watson in the person of Oxford's Prof. Martin Kemp. After the prism the trail divides into lenses and mirrors. Lenses seemed to provide the more promising path via the better documented world of the camera oscura. He splits the world of images into those drawn from nature and those using optics. The former he infelicitously calls 'eyeballed'. He soon realises that even in the case of 'eyeballed' work the experience of merely having seen optically produced images leaves the artist permanently under their influence. This of course offers a major let-out clause when no lens mirror or prism is found among an artist's possessions.

A camera oscura is, literally, a dark room admitting light through a lens which projects an image on to an opposing wall. Without the existence of film to make the image permanent we have to get inside the camera to see that haunting opalescent glow familiar to us from the work of Vermeer. The depth of focus is shallow however and all is brought to the picture plane where the humdrum is transmuted into soft visions of hypnotic beauty. Half the value I would suggest of the camera is that, through the sheer concentration of being in a dark space looking at a single small visual event, it gives you a model of optimum attentiveness; the revelation is that everything if isolated partakes of the whole beauty of creation. Suddenly we all have the heightened awareness of the great painters of still lifes as the closed box opens the doors of perception.

One realises that a kind of silent picture show (TV with nicer colour) was available to artists from the early Renaissance until the chemically produced equivalents became commonplace.

Once experienced these true images acted as a holy grail for artists and according to Hockney transformed in the fifteenth century the practise of painting. The development of the lens to such a capability coincided (all too neatly some might say) with the adoption by van Eyck and others of oil paint. This allowed the gentle gradations, infinite corrections and resonance of colour that made transcription of this optical magic possible.

Enter Mycroft in the person of Charles Falco Professor of Optical Sciences at Tucson who holds a shaving mirror up to nature and provokes another interrogation of the painters of past times. Simpler than the camera oscura the concave lens turns out to project images equally seductive but upside down rather than reversed. Hockney draws a friend as a cardinal using such a mirror (again the drawing itself is less lively than vintage Hockney). The friend must sit outside in bright sunlight (easier to arrange in California than in Peckham ) while Hockney traces the spectral figure indoors before finishing the work off via the eyeball. A few pages later appear the wonderful paintings by Raphael and Velasquez of Popes Leo X and Innocent V respectively. It would be hard to imagine these unindulgent pontiffs permitting an artist to pose them out of doors and then scuttle off to practise witchcraft in an unlit room. Upside down popes would be too Dantesque and the Inquisition would soon be on the phone.

Hockney's test case, Caravaggio, is an artist one feels would have relished secretive methods to achieve his atmospheric theatricals. A wealthy patron and more sophisticated optics would help. Hockney makes out a convincing case for these tableaux being arranged for the camera "like Zeffirelli directing his characters , …'Raise your hand here', 'Put a white feather in his hat' " etc. In the related case of Georges de la Tour Hockney produces a stunning separation of elements in pictures more eloquent than any text to show how such drama could be manufactured.

Does Hockney as Holmes cheat? Well, a little. There are some large convenient omissions and the evidence is sometimes manipulated. In the case of Ingres he juxtaposes worked on studies for portraits where the lensless artist "gropes for the lines". These drawings were for his own use in the context of painting commissions. The Rome drawings, however, were presentation objects and therefore had to show finish in the head and a speedily sophisticated notation for the rest.

Hockney is at his most authoritative where his own artistic discoveries collide with the past. A daring page presents van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece with, above it, his own photographic montage Pearblossom Highway (perhaps Hockney's finest work). Construction and procedure are paralleled to an astonishing degree and the accompanying text (though he seems to mistake the nimbus of the Holy Ghost for the sun) is exemplary.

Other artists are less convincingly introduced. Chardin's still lifes are miracles of space with Chardin paying as much attention to the air between walnut and grape or cup and knife as the objects themselves. Optical projections are notoriously airless. What they register is crammed up to the one dimensional picture plane (as in a Caravaggio basket of fruit).Chardin was the sort of artist who had dark-room concentration without the paraphernalia of optics.

Hockney is a brilliant artist full of humanity, wit and invention. He falls gladly into every trap that art has thought up and some of his own devising, and emerges from each smiling and more sagacious. Yet now as he approaches the bus pass years he knows that, high as he has climbed, the enigmatic summits of art, Titian, Raphael and Velasquez, the league of real genius, still lie beyond and above. He is the first to admit this yet does not quite allow in his arguments for their phenomenal abilities. I do believe that Frans Hals could paint a foreshortened hand in a few strokes, that Velasquez could catch a grinning face and set it down, that Van Dyck could render the sheen on armour and Ingres the patterned intricacies of a folded cashmere shawl and that Durer could make sense of a clump of turf, all without any direct recourse to optics.

Nevertheless when looking at pictures (lavishly reproduced in this no-expense-spared production) one can have no more stimulating and provocative companion than Hockney. Perhaps he has jumped the gun here and produced merely an interim report on his sleuthing but he has asked valuable questions whose freshness art historians might envy.

Having begun with bus tickets I end with a lavatory roll, or at least its central tube. This is my own optic, without mirror or lens. Use it in the manner of a spyglass, isolating the paintings in a gallery from frames or surrounding distractions. You will be amazed to share immediately the artist's viewpoint and vision. In a gallery light sources in pictures argue both with each other and the light source of the room itself. Homing in on a single view you cut out this visual noise. Space doubles: landscapes and still lifes come awake before your single eye. You are in effect bringing a portable camera oscura and pointing it back at a painting. Try it on a Hockney.