Tom Phillips's Introduction to the 5th Edition, 2012

W.H.Mallock in 1907

Page 33 first version, 1966

Page 33 second version, 2010

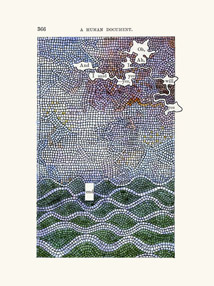

Page 165 second version, 1994

Page 165 preparatory drawing, 1994

Half-title illustration to Dante's Inferno, Talfourd Press, 1983

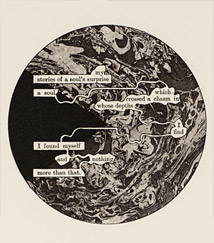

Terrestrial and celestial Humument Globes, 1989 (Victoria & Albert Museum)

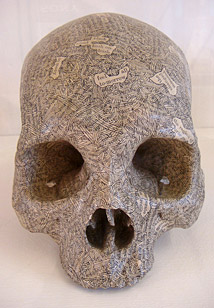

A Humument skull, 1996

Page 4 second version, 2012

Page 366 second version, 2004

Page 9 second version, 2012

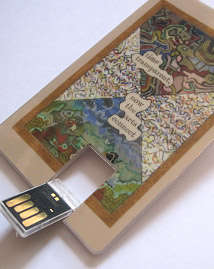

USB: Tom Phillips reads from A Humument

A Humument started life around noon on the 5th of November 1966 at a propitious place. Austin’s Furniture Repository stood on Peckham Rye, where William Blake saw his first angels and which Van Gogh must have passed once or twice on his way to Lewisham.

As usual on a Saturday morning Ron Kitaj and I were prowling the huge warehouse in search of bargains. When we arrived at the racks of cheap and dusty books left over from house clearances I boasted to Ron that if I took the first one that cost threepence I could make it serve a serious long-term project. My eye quickly chanced on a yellow book with the tempting title A Human Document. Looking inside we found it had the fateful price. ‘If it’s a dime,’ said Ron ‘then that’s your book: and I’m your witness.’

It turned out to be a novel by someone that neither I nor my even more bookish companion had heard of, W. H. Mallock. The words ‘ninth printing’ above the date 1892 suggested, however, a certain popularity when it had been published by Chapman & Hall. Fortunately for me, as it turned out, Mallock’s stock had depreciated from three shillings and sixpence at the rate of a halfpenny a year to reach the requisite level.

Mallock was born in 1849 and after leaving Oxford started what promised to be a brilliant career with a rapturously received political satire The New Republic, followed by a stream of anti-socialist polemic and writings on religion as well as many novels. By his death in 1923 he had faded into somewhat embittered obscurity, his views and attitudes all but obsolete. His class prejudice and imperialist hauteur are well on view in A Human Document and his attitude toward Jews (though not untypical of the time) supplies the crux of its love story. For Mallock the adultery of its heroine Irma with Grenville somehow did not really count since her wealthy husband was Jewish.

These aspects of his literary persona assisted rather than impeded my scheme, as did his intelligence, immaculate prose, luxuriant vocabulary and wide range of allusion. In a way his complete lack of humour helped, for it is a pleasure to tease the odd joke out of a novel that contains almost none.

Like most projects that end up lasting a lifetime this had its germ in idle play at what then seemed to be the fringe of my activities. A liking for words plus the related influences of William Burroughs and John Cage with their use of chance had led me into casual experiments with partly obliterated texts, mostly in the columns of The Spectator. By the date of the encounter with Mallock I had already begun to toy with the idea of treating a book in the same fashion. Now the die was cast, the dice thrown: chance had become choice and a notion grown into an idea.

Once I had got my prize home I was excited to find that page after randomly opened page revealed that I had indeed stumbled upon a treasure. In my eagerness of darting here and there I somehow omitted to read the novel as an ordered story and, though in some sense I almost know the whole of it by heart, I have to this day never read it properly from beginning to end. Nonetheless, from that time on, whenever I have had a problem of providing a text for some artistic purpose, be it grave or trivial, I turn to Mallock first.

It was while I was experimenting with ways of combining pages that the book’s christening took place, again by a chance discovery. By folding one page in half and turning it back to reveal half of the following page, the running title at the top abridged itself to A HUMUMENT, an earthy word with echoes of humanity and monument as well as a sense of something hewn; or exhumed to end up in the muniment rooms of the archived world. I like even the effortful sound of it, pronounced as I prefer, HEW-MEW-MENT.

In the early days I merely scored out unwanted words with ink leaving some (often too much) text to stand and the rest more or less readable beneath neat rapidograph hatching. The first page I finished in 1966 was p33, whose revised version makes its appearance in the fifth edition (2012). Reworking it I have incorporated part of the original as a memorial to the start of things, burned and pasted on to its successor. I discovered in the process some new words above: ‘… as years went on you began to fail better.’ This hoped-for truth incorporated a phrase of Beckett I have used elsewhere, but which did not exist until seventeen years after my initial treatment. Serendipity is my best collaborator.

Soon a hidden hero emerged from behind the columns of text to interact with the novel’s actual protagonists, and to make a contrast to them in class and style. Since the W in W. H. Mallock stands for William, its commonplace short form, Bill, would provide a good matey name for his more humdrum alter ego. When I chanced on ‘bill’ it appeared next to the word ‘together’ and thus the distinctly downcast and blokeish name Bill Toge was born.

It became a rule that Toge should appear on every page that included the words ‘together’ or ‘altogether’ (as indeed befits a doppelgänger). The intended pronunciation is ‘toe’ (as part of a foot) and ‘dge’ (as in ‘drudge’ or ‘fudge’, two words redolent of the artistic enterprise). I have heard it variously pronounced, but Bill Toge seems about as unfancy a name as you can get; as are those of the anti-hero’s friends who make guest appearances (Eve Sardine, Ted Wink, Stan Gage, Mrs Mornspot et al.). Toge’s story, a little less glum now than in the first edition, is the non-linear narrative of one who has a somewhat bumpy ride on the roundabouts of art and love.

In a work such as this it is necessary to have some rules, and as far as I know the condemned presence of Toge on the relevant pages, after he takes the stage on p9, is a rule never broken. Nor, more importantly (for otherwise the whole task would become too casual and easy) are there any but the smallest divergences from a general imperative that Mallock’s words should not be shunted around opportunistically: they must stay where they are on the page. Where they are joined to make some poetic sense or meaningful continuity, they are linked by the often meandering rivers in the typography as they run, with no short cuts.

Occasionally the rivers in the type are not only used to link words and phrases (to avoid a staccato effect except where wanted) but are brought into play to make drawings, usually a face or a figure (as illustrated here on page 165, second version 1994).

By 1973 I had worked every page. The finished book was shown within weeks of its completion at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (in whose bulletin it had first been mentioned, by Jasia Reichardt, and a page from it illustrated, in 1967). It was shown the next year in an exhibition that travelled from London’s Serpentine Gallery to the Gemeente Museum in the Hague and ended up in Basel. There, at the Kunsthalle, it was seen by Ruth and Marvin Sackner, who were to become the owners of the whole manuscript as well as keen supporters of the continuation of the project.

Seeing the book shown as a whole (and in this state being issued in the loose sheets of Ian Tyson’s Tetrad Press edition) gave me some satisfaction, but the feeling that I could fail better than that began to nag. The first bound trade edition (1980), prepared by Hansjörg Mayer in Stuttgart and distributed by Thames & Hudson, marked the end of a dormant period. The book had become a book again and in its turn a suitable case for treatment.

I had originally avoided introducing outside material, thinking to keep the work ‘pure’. Since, however, Humument fragments crept in to almost everything I did, I felt the urge for reciprocal action and began to incorporate motifs and collaged imagery from other aspects of my work. In the original introduction I spoke of ‘mining and undermining’ Mallock’s text but I was now aware I had not dug as deeply as it might permit. Thus the first version could be regarded as preliminary opencast mining leaving more hidden seams to be investigated.

So I set about doing the whole book again, showing bit by bit, as edition followed optimistically imagined edition, what I could come up with. A few of the original pages however resisted reworking: I had grown fond of their words and designs. Occasionally I am content in such cases merely to redraw them with only slight variations. As I revisit and revise I begin also to imagine some eccentric scholarly recidivist one day making a Variorum Edition, bringing together all the multifarious word clusters I have contrived.

As early as 1969 the novel provided not only the libretto for the opera Irma but its stage directions and design brief. In the seventies it also served to accompany many series of watercolours, largely based on postcard sources, such as Ein Deutsches Requiem, The Quest for Irma and Ma Vlast. The most elaborate of these excursions was the long suite of illustrations to Dante’s Inferno in which Mallock provided an excellent foil to the all-knowing Virgil. Here at the opening of the volume some blank verse echoes the metre of my translation.

This process has continued over the years, with Humument fragments providing gores for fictitious globes (now in the Victoria & Albert Museum) or decorating both the inside and outside of a skull. Most recently excerpts have decorated the covers of an ongoing set of books prepared for the Bodleian Library from my archive of vintage photo postcards, and in 2011 (once more on commentary duty), accompanied an illustrated edition of Cicero’s Orations made for the Folio Society.

However diligent the compilers any such an omnium gatherum might turn out to be, there will always be scraps and shards that elude them; a trivial greetings card here, a record sleeve or CD cover there or even a faded T-shirt at the bottom of a drawer.

It is, after all, my resource of greatest use – and all thanks to a man who, from photographs and contemporary accounts of his personality, would seem to be someone I would not at all have enjoyed meeting.

I have so far extracted from his book well over a thousand segments of poetry and prose and have yet to find a situation, sentiment or thought which his words cannot be adapted to cover. That Mallock and I were destined to collaborate across a century became quite clear when I tested other fictions and discovered nothing to equal him in the provocation of fresh conflations and conjunctions of word and phrase.

How this serendipity has worked is well illustrated by the result of a recent urge to react in some way to the catastrophe of the twin towers in New York. Many years ago I had a concordance made (largely by Andy Gizauskas) of the whole novel in a little notebook now frayed and stained to the point of unusability. This has recently been replaced by an electronically created version masterminded by John Pull and smartly bound, which I duly searched for the unlikely occurrence of ‘nine’ and ‘eleven’ on the same page and in the right order. To my amazement I found them, on p4.

As has always been my practice I look for a text first and let its disposition condition any imagery that is at the back of my mind. In this case I scanned the page on the lookout for apposite commentary. I recalled the event’s uncanny prefigurement in the Inferno where Dante compares the giant Anteus to the skyscrapers of his day, the bristling skyline of 13th-century Florence with its many tall and narrow towers. A postcard of King Kong was already featured clutching at the World Trade Center in A Postcard Century, as was a version of Goya’s Saturn Devouring his Children. These pictures were thus ‘pasted on to the present’ as the text suggests. The accompanying Roman numerals make a twinning palindrome and their non-arabic presence suggests the ‘time singular’ also mentioned. Thus classical mythology joins medieval poetry together with an early 19th-century Spanish painting, a Victorian novel and a 20th-century American film, combining to link late modern architecture to a 21st-century disaster.

Few pages are as complex in their devising as this one, yet, even though a lot of the book is intended as a diversion, there is a current of reference to literature and music throughout. I was specially thrilled, right at the other end of the book, to extract from the penultimate page the closing mood and actual words of Joyce’s Ulysses with the famously repeated ‘Yes’.

To a great extent this amenability in providing text after text comes from the typography and layout of the one-volume edition that I have been using. As was the normal practice of the time A Human Document made its first appearance as a luxury three-decker. When eventually I found a copy of this the whole story, spread over three volumes, looked very aerated, with highways rather than rivers through the type.

A particular curiosity (that has led some transatlantic commentators to accuse me of serial cheating) is the single volume American edition, also of 1892; in this, tricky foreign phrases are suppressed, so that words become quickly out of step with the British edition, setting up quite a different field of possibilities for a whole new work (given a whole new lifetime to do it in).

Inasmuch as A Humument tells a story it could be described as a dispersed narrative with more than one possible order; more like a pack of cards than a continuous tale. Even in the revision, I still do not tackle the pages in numerical order. A narrator, unreliable as is fashionable in contemporary literature, has most of the text. Sometimes he might be identified with the artist and sometimes not: and sometimes in any case it could be a ‘she’.

As well as words with meaning I have enjoyed the discovery of nonce or nonsense terms which provide a fantasy obbligato to the measure of the text. These are extracted from longer words. The less self-evident their source the more autonomously real they can seem, as on p46 where ‘derstan ansfig’ are ‘the last words on earth’.

This is only an extension of the more frequent practice of extracting sense from sense as on p1 where ‘sing’ is detached from ‘singular’ in order to provide the necessary formula for the launching of heroic, or in this case mock-heroic, tales. Here the words echo the beginning of Virgil’s Aeneid, ‘Arms and the man, I sing…’ (Arma virumque cano…)

In the years since Mallock wrote his novel the English language has itself sent out new shoots. He could not have imagined the future use of ‘plane’ for example. Similarly at the beginning of my own endeavour I could not have predicted the dark resonance that ‘bush’ has come to have or how a simple word like ‘net’ would grow immeasurably in significance. Suddenly in 2011 I can find on p9 both ‘app’ and ‘facebook’, which would have had no meaning at all even ten years ago, not to speak of that grim conjunction already mentioned of ‘nine’ and ‘eleven’, once inert but brought to sad life by so much death.

The original copy of A Human Document that I started out with in 1966 was worked on without destroying any of its pages and is now, intact in its original binding, housed in the Sackner Archive in Miami. Unlike this integral and somewhat fragile version the revised pages have been worked on using one side only, mounted on acid-free paper to make them not only more durable but easily frameable. These originals have also largely found their way to Florida. Another copy has stayed with me in which are noted the dates of completion of each revised page and any variant fragments of it that have been used. Yet another whole copy went into the making of The Heart of A Humument (1985), a miniature book extracted from the middle of selected pages.

This accounts already for five copies and, in the production of various fragments, I have made substantial inroads into at least four others of the one-volume edition. Many have been sent to me by well-wishers, notably that miglior trovatore Patrick Wildgust. Others were bought by me at a time when the book could be more easily found and had not attained the price it now fetches (which can be anything up to £80). Although that original book was unmarked except for its pencilled price and the signature of its former owner the pooterishly named Mr Leaning, others feature a little more bibliographical information. One was purchased at the Beresford Library, Jersey, in 1898 by Colonel J. K. Clubley and passed into the hands of someone who merely signs himself ‘Hitchcock’. Another came from the library of a past president of the Royal Academy Sir Gerald Kelly (whom I once met when a schoolboy in Dulwich) though how he got it from ‘Nell’ to whom it was presented by ‘Michael’ in 1901 is not recorded.

Lest I should think myself the first to doctor this work I happened upon a copy (coincidentally from that same furniture repository in Peckham, this time for one shilling and sixpence) that had belonged to Lottie Yates who had herself treated it with much heavy underlining and word encircling that seemed to reflect her own Togeian romantic plight, sighing into the margin from time to time ‘How true!’ It seems also that she had used it as a means of saying to her beloved the things she lacked words for, passing the marked copy to him as a surrogate love letter. Thus in 1902 someone had already started working the mine. Most intriguing is a copy not in my possession but among the books belonging to Oscar Wilde in the library of Magdalen College, Oxford, whose librarian notes a perhaps significant stain, possibly made with jam, on one of the pages.

The publication history of A Humument is not without bibliographical byways after the first of those ill-fitting boxes in fugitive colours appeared in 1973 from the Tetrad Press. That publishing venture, heroically undertaken by Ian Tyson, was beset by economic crises as the subscribers dwindled in number, and pages destined to explore various printing media were hurriedly finished photolithographically. A full account of initial publications (including variations I made of p85 in an effort to demonstrate the inexhaustible nature of Mallock’s text) will appear in due course on the appropriate website.

A Humument has always been a kitchen table task, initially in Camberwell, then in Peckham, and occasionally in recent years in my apartment at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton where I am writing this. It has also been almost entirely an evening employment at the end of a studio day.

In an earlier rendering of this introduction I grandiosely described A Humument as ‘a Gesamtkunstwerk in small format’. Perhaps now with its various by-products, recyclings and revisions it really does aspire to that lofty Wagnerian formula of the comprehensive work of art. The App version for iPad and iPhone can also be employed as an oracle with appropriately random access and suitably cryptic advice. There is also a purchasable USB card, offering a miniature son et lumière event that can slide into a wallet next to student ID card or old folks’ bus pass. This piece of illuminated plastic bears both Humument pictures and their spoken text. A full Variorum Edition may remain a dream (or a posthumous project) since the wheel is still turning and the odd spark still flies off.

For the time being I must try to get to the end of the revisions and deal with those pages which have so far evaded change, especially the ones whose original solutions have stood up to almost fifty passing years. I retain the option of leaving them as they are, thereby forestalling the absolute end of my venture, even if hanging on to the book in such a way may be thought a suspect strategy synonymous with hanging on to life itself.

I once combed the churchyard in the town of Wincanton where he died for the grave of William Hurrell Mallock, thinking to put some flowers of gratitude upon it. I failed to find it however and must keep unredeemed some apprehension of guilt at having ransacked and upturned his writings like a wrecked room, subverting them to say things that would have dismayed and disturbed him. It may happen though that one particular page might stand unchanged to do service, not without a degree of irony, as a curiously mutual epitaph. He might desist from turning in his undiscovered grave at the thought that he has been in some way perpetuated through me as I through him.