Tom Phillips

By talking of the picture as an improvisation I seem to deny the existence of any preparatory work. In a sense, apart from the choice of the initial panel, there was none. The underpainting of the panels as can be seen is inconsistent and wilfully random: they are provocation rather than preparation.

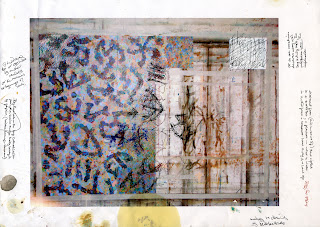

All painting, since it takes the form of replacing nothing with something, is improvised if only by stealth. So yes, even here a bit of tentative drawing does go on slightly ahead of the brush. I snatch a piece of card that won't soak up oil paint too quickly and rehearse some marks on it. Here is a card currently in use with apologies to the designer bookbinders whose private view invitation it is, or once was.

Another strategy is to print out a photo of the painting in its current state and try out possible next moves on that. This is one I had pinned on my study wall in Princeton: it features also an initial idea of what might happen in the top left hand panel when it was replaced.

These are utilitarian drawings of the kind that, rather than featuring in exhibitions, usually find their way via the studio floor to oblivion.

All readers of this blog are invited to attend the private view at the Williamson Art Gallery and Museum, Birkenhead.

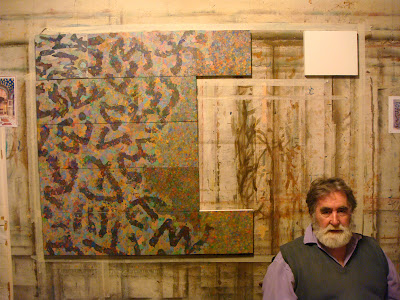

State of play at Christmas 2007. Still no title. Too many analogies present themselves. Today I felt as if I were cleaning a picture which has long existed, moving along a murky surface to reveal a work obscured by time's dirt and decay. Sculptors often (as in Michelangelo's poem) say about carving in marble that the imprisoned sculpture has only to be released from the stone by chipping away the bits that are not it. Here in two dimensions I seem to be working in positive/negative modes taking my cue from what is light to make it dark and vice versa. Together with the ambiguities of the underpainting left untouched this seems to make Time's Arrow turn back on itself.

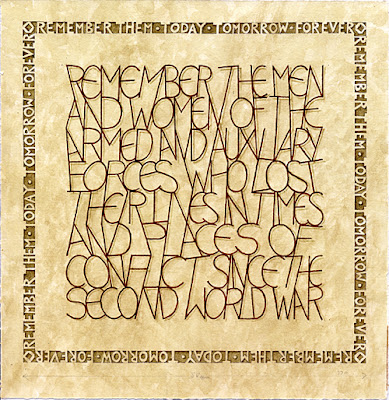

Preliminary study for Armed Forces Memorial, to be installed in Westminster Abbey.

Meanwhile a work emerges from two years of revisions, changes of size, alterations of site, rewordings of text, and colour, switching of materials and reversals of method; all subject to debate within various committees of both church and Ministry of Defence. This not to mention my self-inflicted labour on battle sites of the past, digging up mud from, inter alia, Agincourt and the Somme and, most recently, at Princeton where a handy slice of the War of Independence was thoughtfully fought a few yards from Einstein Drive [you can't win them all].

The work in question is to be installed in Westminster Abbey, on the cloister wall, later this year. It is a War Memorial (sorry, Conflict Memorial, since we don't have wars any more) constructed of metal, earth and stone. The metal is welded copper and the border lettering is cut into the cloister wall itself. The earth is a mixture of the aforementioned mud of which blobby packages have been arriving from my daughter and, via a friend of a friend from Asia to augment my already large selection, now appropriately ranked in uniform storage jars.

Despite the long reversals and delays I am happy with the outcome especially since I was allowed to change all the wording from an initial committeespeak version. Most of all I am proud to have my work present within singing distance of the mysteriously intricate Cosmati pavement (a miracle seen from above) and the gravity-defying fan vaulting (a wonder seen from below).

The highlight of the committee stages was when I presented the preliminary designs as seen here to the memorial board at the Ministry of Defence to enter whose premises (though only armed with a watercolour drawing) I was podded, checked and scanned. After an extended and largely approving discussion a puzzled army officer of very high rank said "Well, I've been looking hard at this and feel... I'm no art expert mind you... that I ought to point out that the writing is a bit wobbly." It was as if he had expected letters to stand at attention when he inspected them.

Since this painting daily commands most of my attention it comes to act as a repository of my energies; not a locked chest, but one that continually leaks to affect or, in viral fashion, to infect other work in progress. Even some innocent portrait may show symptoms. However it is A Humument that always falls first victim to such benign contagion, as can be seen in the most recent of the reworked pages. The book as a whole provides a lifetime diary of tropes and trends, strategies and devices, a house of memory of my visual preoccupations.

A Humument page 7, 2007 (click image to enlarge)

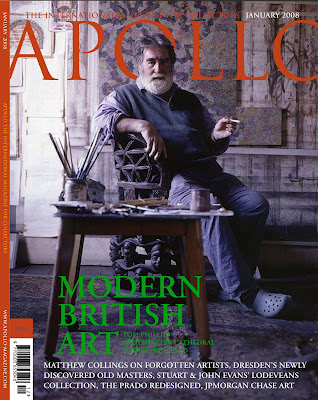

The photos of my picture and its crazed-looking creator that have appeared in this account were taken by Alice Wood. The present state of the painting in a slightly wider studio context can also be seen here through the lens of Lord Snowden, as featured on the cover of the forthcoming issue of Apollo.

Humument page 233 (click image to enlarge)

Tom Phillips will talk about his work in conversation with Patrick Wildgust (curator of Shandy Hall) on January 4th at the opening of his forthcoming exhibition at the Williamson Museum and Art Gallery.

Pictures as they progress tend to generate rules; rules of inclusion and rules of avoidance. Abstraction has the problem it sets itself of shunning representation or likeness. As the work develops, a deliberate and authentic breaking of such a rule can be a daring and stimulating manoeuvre, whereas an accidental infringement (a sudden unintended face-like image in a non-referential picture, for example) is merely bathetic.

While I was in Princeton my painting was in Peckham. I did however take with me a print-out of the state I left it in. I pinned this on the wall as soon as I arrived and looked at it every day. I saw that something was wrong but resisted the thought that the part I held most precious was now it's chief impediment.... how often and sorrowfully this turns out to be the case.

The top left hand corner panel, the little painting that had seeded the whole enterprise, was behinning to stick out like... but what if the rest of the hand was sore and the thumb quite healthy? Somehow it seemed now an anomaly in the dance of signs that the work had become.

I made some tests by cutting that segment out of the copy and supplying other marks on a piece of paper pasted in the space. This appeared to help the rhythm of the other elements in their spatial movement.

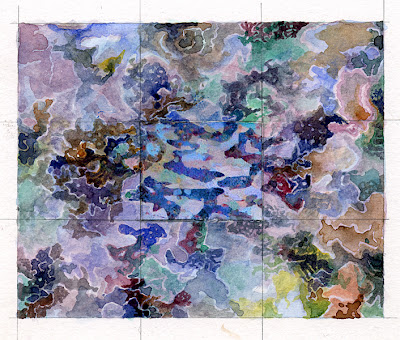

The little rectangle (1 1/4" x 1 1/2" approx) I pasted on to another sheet of stretched paper and surrounded it with eight equal spaces. I found that it naturally generated pictorial matter around itself as in the watercolour sketch below.

Perhaps it might go on forever serving to seed paintings from which it would have eventually to be itself banished....

...

Returning to Peckham I start to feel my way back into the picture. For the moment I have not renewed the panel in question, but, as a gesture have turned it upside down as a reminder of what to tackle soon.

Princeton improvisation, watercolour and xerox, 3 1/2" x 4 1/2". 2007

A Humument p4, 1967 and 2007 (click image to enlarge)

As dawn broke on the day of my show’s opening at Flowers, Madison Avenue, I crossed the road from the Chelsea Hotel for my usual breakfast at the Malibu Diner, and, as usual, bought next door a copy of the London Times. My cheerful mood was dashed by reading news of the death of an old and dear friend, RB Kitaj.

As I made my way on foot for fifty blocks, in stages broken by coffees and lunch, to the gallery I thought of old and more innocent days, especially the long Saturday mornings we spent together at Austin’s of Peckham (Ron was then living in nearby Pickwick Road). There, opposite the place where Blake first saw angels, we rummaged amongst old books or hunted for some unnoticed old master etching in that furniture repository’s ritually revealed new stock. It was there also that I bought (on October 14th, 1966) for threepence, the copy of A Human Document, a victorian novel bound in faded yellow buckram which would soon start its second life as A Humument. With Ron as witness I vowed to work on the book for the rest of my life.

By the time I got to 75th St I had thought of a small way to commemorate my friend at the exhibition. The latest page of A Humument, a reworking of p4 to replace the original version of 1967 was in the gallery's back office. The best thing would be to pin it on the wall with a notice underneath dedicating it to Ron’s memory. This I did; to show his ghost that I had kept my word.

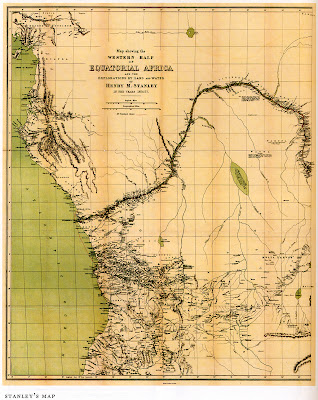

There is much talk of a map at the beginning of the opera. On a visit to the Firestone Library of the University, Julie Mellby the Graphic Arts curator guided me through an intriguing show of African cartography. And there, in the equatorial section, was the exact depiction of the Congo that Conrad must have been referring to 'like an immense snake uncoiled'. This was Stanley's map full of what Marlow calls 'places with farcical names where the merry dance of death and trade go on'. It will now become a fixture of the set, seen three times in varying sizes. One of the bonuses of curating an exhibition is that one can never know what particular exhibit will spark off an enthusiasm in someone wandering through, or what almost unasked question it might answer.

The highlight of my month in Princeton had, of course, to be my return match on the ping pong table of the astrophysics department between Herman, a genial giant who works in the mail room, and myself. I yielded my hitherto undefeated record to him on the last day of my stay in 2006. On the last day of this visit I won by three games to one. Eric Maskin, of whom I made a drawing last week, could not have been more delighted when he learned of his Nobel Prize.

Meanwhile in Princeton and New York Heart of Darkness edges like Marlow's boat towards a healthily receding resolution. Two first performances of a full piano version have now been given, the first at the Institute for Advanced Study and the second in the much smaller hall in Brooklyn of American Opera Projects. Fiona on a warmly welcome flying visit graced the Princeton event, as did Ruth and Marvin Sackner.

Tarik and I did a short stand up routine before the performances, he giving some examples of earlier treatments and I describing a fit-up set (with photos by Billie Achilleos [as above] of the tiny paper model I had designed). This set (structured for robust touring to small theatres) has somehow become part of the promotion.

Rehearsing it and hearing it twice (under two conductors, Steven Osgood & Oliver Gooch) gave Tarik and myself proper opportunity to consider cuts and pastes and changes that could be made before its next outing in London, possibly in the spring with Covent Garden's Genesis Project.