Tom Phillips

As at 30th May '08

My 71st birthday, and a couple of days off spent with F in Florence in the splendid apartment of generous friends. Sitting here on their terrace I can see among the famous silhouettes the top of the building that I drew sixty years ago when, propped up in a hospital bed, I copied an illustration, itself no doubt fairly crude, of Giotto’s tower from a book. I still remember the excitement of having a fine sheet of white paper on which, with a mapping pen and sticky Indian ink, I followed the fascinating lines of the decorative façade. I suspect it was the first thing that I had made that I thought of as art… a special piece of paper with something special on it.

It was a one day wonder in the ward and considered by nurses and fellow patients to be amazingly (I remember the word most often used) ‘lifelike’.

I’d no doubt blush or smile to see it now. But what would my eleven year old self think were he to open his future studio door and see the painting that he is doing in 2008? He might well be amazed, even dismayed, though 'lifelike' would be the last word he would reach for.

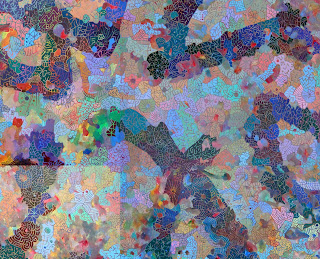

Lifelike, however, is a term that has gained in amplitude. Our image bank now contains the galactic choreography revealed by the Hubble telescope and the organic dances that, in miniature parallel, are presented by electron miscroscopy.

We begin to apprehend a unity in the cosmos at the visual level. Open any scientific journal and it is hard to tell without reference whether any illustration is of an infinitely large or infinitely small event; especially since they are made cousins by the current taste for schematic colour coding.

To be armed with this larger license as to what is lifelike becomes as frightening as it is exhilarating. Even the panels supporting my picture teem with inorganic activity as, in all directions and without end, subatomic particles ping and caper about through its inert-seeming fabric. On top of this my picture is a battleground in which delicate manoeuvres in suspended combat combine to describe a hesitant moment of a situation in flux.

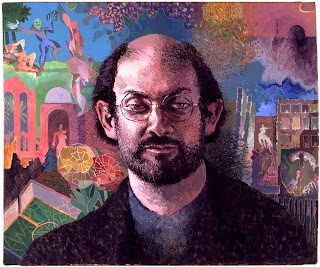

Photo: D.S.

Looking again across to Giotto’s tower I register that it is itself lifelike. Its austere intricacy, perfection of marble interval and balanced dialogue of dark and light, mirror platonically something of the structure of the world.

Having called these notes (as republished in Turps magazine) The Biography of a Painting, I have implied yet another version of lifelikeness. The history of the picture’s making is the story of its life, its moving through time to a close. Since I am edging on to the final panels it more and more resembles my own life which has a great deal more past than future. Unlike human existence however it invites revision and, at the end of the last panel (having closed off in one sense the future) I can go one better than nature and reopen the past.

As at 9th May '08

Over the next few weeks progress on my painting will slow down as more studio time is taken up with The Magic Flute, now only six weeks from opening night.

The long all-licensed time of fantasy is over for director Simon Callow and his designer when they could hoot and bray and throw their toys out of the playpen. Now the Real People take over, the technical team armed with hammer and needle, tape measure and plan. Impressionistic schemes must be turned into reliable structures and scribbled drawings develop into feasible costumes.

Sketches like these have to be carpentered and painted to make practical doors in a firm wall.

First study for back wall with nine doors, Act 1

First study for back wall with nine doors, Act 2

Making proper working drawings which answer the questions, how thick, how high and what precise colour, is my current task.

Somehow panic strikes every production as if it were a necessary ingredient to theatre. Keeping up with Simon's quicksilver shifts of notion and scheme has provided the excitement so far. Now all must be transformed into low budget reality.

So it must have been with the mercurial Schikaneder, the performer, librettist, director and impresario whose original show this was. Who else would, within the first five minutes, have a Japanese prince attacked by a snake and rescued by sinister veiled ladies, then left to exchange existentialist repartee along the lines of Waiting for Godot with a man very like a bird.

Sarastro's emblem<

Some details can be fun to do. Here is (for the Parsifal aspect of this multi-faceted piece) Sarastro's emblem of office, a freehand drawing to be enlarged and printed on cloth. As a perk of the job I will get the wardrobe dept to produce a T-shirt similarly emblazoned to add gravity, power (and maybe some magic) to my ping pong.

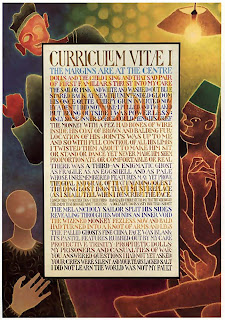

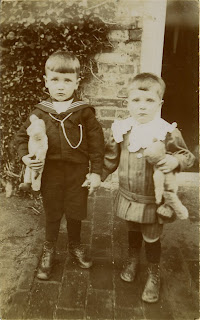

Here with the two boys and their schismatic teddy bears, Mahomet and Ali, is the companion card, My golliwogg’s called Jesus. The double ‘g’ at the end of the word is the original spelling in the illustrated stories of Florence Kate Upton published just before the end of the nineteenth century. Bears existed as dolls at that time but were named Teddy after Theodore Roosevelt in 1902 when he seems to have spared a bear on a shooting trip (during which presumably he killed lots of other things). Both gollies and teddies were at the height of their popularity when these photographs were taken by their anonymous postcard photographers around the time of the First World War. I had one of each as a child in the Second World War, among other worn, handed down dolls, three of which are described in Curriculum Vitae I.

Curriculum Vitae I, Oil and acrylic on board, 150 x 120 cm, 1986-1992

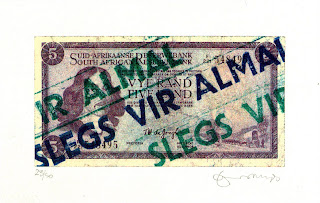

Except for CND marches in the fifties and, during the struggle against apartheid in South Africa (when I joined a group which showed internationally under the heading Artists Against Apartheid), I have not been much of a political activist.

Slegs Vir Almal (Reserved for everybody), Silkscreen, edition 50, 1976.

I mistrust all ideology and even managed, though strongly influenced in matters musical by Cornelius Cardew and John Tilbury, to dodge the Red Dawn Rising Over Luton. In fact the only card-carrying political affiliation I have had is with Clapham Young Conservatives having early discovered that their ping pong facilities were much superior to those of the Young Socialists.

Ping pong diplomacy did not end there. Salman Rushdie, at the height of the fatwa, adopted a deliberately irregular routine, with much cloak and daggery in the coming and going, of portrait sittings combined with ping pong and pizza. The story of the teacher and the teddy bear brought back memories of that passive activism; of painting Salman, sometimes with an armed guard in the studio and always with heavy back up outside.

Salman Rushdie, Oil on canvas, 50 x 60 cm, 1992

When illustrating my translation of Inferno I also made a picture of both Mahomet and Ali, to whom Dante gives such short and brutal shrift in Canto XXVIII. That was in the early eighties and then one hardly needed to give it a second thought.

Current Islamic orthodoxy bans depictions of the prophet. This applies to Moslems of course, but cannot to those who hold other religious beliefs (or no belief at all). Why shouldn't other faiths, sects and cults claim equal rights to make their rules apply to all? Overwhelmed with a Swiftian deluge of observances we might soon be struggling to remember if the Ammonites decreed that we should wear a funny hat on a Tuesday or if the Theodolites commanded that we should not eat turnips in June.

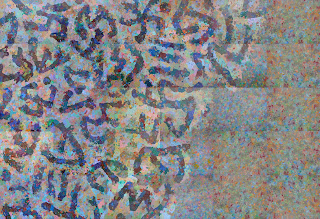

My painting XV

As at 9th May '08

I return to my painting, if only to note ironically that it shows the clear influence of Islamic calligraphy. It was precisely these strictures against description of the natural world that made the finest Islamic artists probe the expressive possibilities of script and bring an often sublime inventiveness to enrich to the art of the world.

Early May 2008

Although I shall still put 'My Painting' at the head of these instalments in the biography of a picture I have, at long last, found a title for it. Of the many words that have been churning around in my head two have come to rest together and seem to sum up what I think I am trying to do. QUANTUM POETICS is a juxtaposition which may even contain or conceal an unexpected truth. Unfortunately 'quantum' is a term much thrown about these days and needs to lassoo a tough qualifying companion to validate its use.

It would not take long to write out what little of the little that is understood of quantum dynamics I myself understand. Luckily however, in my own world, thought is often pictorial and imagery occupies the place of verbal or mathematical analysis.

Daunting explanations in print and conversation, while indeed enabling me to have a partial grasp of actualities, generate at the same time more freely formed embodiments in visual terms. These often link to the intuitions of the past which, in pattern and design, for 70,000 years have expressed things that were not ripe for use or available to knowledge.

Thus I am reminded again of how much human thought has been secreted over millennia in the rich resource of ornament. It was there for example that abstraction waited patiently for the twentieth century to discover and realise its riches.

Perhaps an imaged response might even have a modest purpose. What it can do is to try to articulate a part of that field of wonder that recent science has revealed, and which the art of the past had fragmentarily intuited. This picture is but one hesitant attempt at such a non verbal commentary, a contribution to the beginning of a poetics of quantum theory.

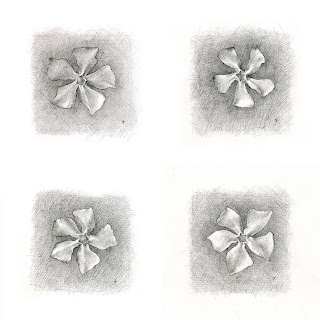

On the last day of April I drew the seventh and final periwinkle of this year’s Periwinkle Diary (see Blog April 2007) started in 2006. Nothing like a quietish pencil drawing from nature to steady the mind and hand. Now that I have more or less retired from portrait painting I think to get back to life drawing (where all the ladders start); when I find the right model. Meanwhile the periwinkle is an uncomplaining substitute that needs neither rests nor cups of tea. All these periwinkle flowers are, for the first time, homegrown (tended by Megan in the front garden), so no raiding Ann's display up the road. Here are four of the current crop.

Late April 2008

Peter K asks whether I’ve found a title yet, having noted my reticence about that problem lately. Well, almost, I think, as the work itself moves quietly on. Strangely enough while this picture stands in need of a title I spent most of last Sunday at the Bloomsbury postcard fair with a title that is in search of a picture.

In the vein of the exhibition We Are The People, where I showed a sample of my embarrassingly large collection of old photographic postcards, I have one card which shows two anonymous boys with their teddy bears, which I want to use for half an evenhanded diptych. It will be entitled ‘Our teddies are called Mahomet and Ali. They are always fighting’. This refers of course to the glum affair in Sudan where a teacher was imprisoned for allowing her pupils to call a teddy bear Muhammed, the world’s most common first name.

The other half of the diptych calls for a postcard image of a similarly anonymous girl holding a golliwog, the title of which will be ‘My golliwog’s called Jesus’.

I did in fact find one card that may be right. In case a better turns up I’ll wait to put it up until the next entry at which time I will also divulge the title of my painting, on which multiple cliffhanger…

Mid April 2008>

How predictable is the unpredictability of art and the artist....

No sooner had I vowed to move forward, leaving unresolved areas to the end, than I was scuttling back to the middle South of the painting, to the chief disaster area where a calligraphic motif has been quietly strangling itself for weeks; an event that was robbing the work of much of its rhythm.

An interim operation brought immediate relief, though this kind of surgery is difficult since a new tracery has to be teased out of the old in negative fashion. Scraping back to the underpainting seems not to be allowed: I don't know where such constraints come from or why I declare myself not free to use any strategy I fancy. It is yet another aspect of the picture's tendency to dictate terms and my own tendency to accede to its wisdom. Perhaps the painting is protecting its own integrity of surface, an imperative in art from Cimabue to Jackson Pollock and beyond.

Also it needs to guard its nature as a composition, which is that of a continuum. Apart from the early radical gesture of replacing the North East corner panel, all procedures have been additive. The rightness of this current emendation was proved by how, once the incision was complete, the separated section floated free; like a released balloon.

as at April 8th 2008

I begin to suspect as I forge on eastwards that I leave too many worries in my wake; a mounting toll of passages which do not quite work. Some I will no doubt be able to nudge into life while, with others, I can lean on my favourite Zen mantra, These problems will tend to disappear. There are however one or two trouble spots that, in that fine imagined last westward sweep of revision and adjustment, might continue to prove intractable: yet my instinct (which may well be cowardice in disguise) tells me to move on.

Every picture has its puzzle-solving crises and needs, at some juncture, either a small but daring manoeuvre or a grand gesture (eg turning the whole thing upside down). To proceed unchallenged is as unsatisfying as beating a weak opponent at chess, or breezing through a Sudoku in merely the time it takes to fill the squares.

A good Sudoku however, will usually bring one to a point of exasperation, after which miniature agony one suddenly spots the critical move and all remaining numbers tumble into place. So with the picture I trust to the late intervention of the Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke to crack the problem.

It is not irrelevant to invoke Richard Dadd since this painting too has its lunatic aspect. Its dogged intricacy has much in common with the art of the mad, as Harry Birtwistle (himself only just released from the million-note labyrinth of a new opera) was quick to remark last week when he came to take a look at the picture.

In art you have a chance to repair the past so it’s forward ahead for the harmless artist self-sectioned in his studio and clinging to the words of William Blake… If a fool would persist in his folly he will become wise.

Early April

To get oneself talking, ask oneself a question. One reason for laying down the splodgy field of random colour is to have something to respond to other than the frightening white of a newly primed panel [see the unworked panel here in the southeast of the painting ].

Even as a child my first instinct was to mess up the paper before beginning, hoping to find in that mindless confusion of runny posterpaint some suggestion of event. Although I did not know it at the time this is Leonardo's recommended method for the young artist whom he instructs to gaze at a stain on the wall until landscapes emerge and are peopled with figures.

With my painting, by perverse extension, I set up one abstraction to feed another.

In addition to banishing the virginal white [the only time any picture is perfect] I thus drive away the fear of finding no colour in my head.

For I am not one of nature's born colourists. Just as at art school there will always be, amongst one's fellow students, one that cannot make an awkward or ugly mark there will be another who is tone perfect… I can see her now… she has put down a vibrant crimson and is mixing some kind of twilight blue… and yes, it nestles against the red. Each makes the other sing… and now a yellow green satisfyingly completes the chord.

Such harmonic certainty one can but envy and congratulate, and then pass on to find one's own mode of plundering colour's endless resource. The same has been the story in my musical life where I have struggled to attain even a modestly reliable sense of relative pitch.

It was through music in the early sixties that I found release. John Tilbury was my mentor and through him I became friends also with Cornelius Cardew, Christian Wolff and most especially with Morton Feldman. I learned to value every and any combination of notes and timbres. So, by analogy, I saw that there were no colours that did not go together. Each conjunction has a character and reverberative identity to be sought and used. To free myself further from the Euston Road I also used chance (via the I Ching via John Cage) to trap myself into making bolder decisions.

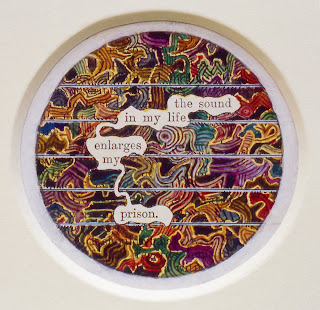

I found my motto in the usual place – the inexhaustible pages of A Human Document.

The process of mining such fragments from Mallock's text, I suddenly realise, is the mirror image of making this picture; working over the colour field, selecting parts of it and using the shapes that eventuate. With A Humument I am of course, by mining his field of verbal colour, standing on someone else's shoulders, whereas here in the painting (despite the anatomical difficulty) I am standing on my own.

In music one plays best by listening, even just to oneself. When I'm improvising at the piano (the only kind of playing I do these days) it is by hearing some shift in the bass that I am made to divert the right hand from what it was poised to play and reach for something more inventive. I am not much of a pianist so I need my own self to give me all the help I can get, and then not to be afraid to take it.

Slowly one makes progress. I used to be scared of yellow which I never seemed to be able to control. Now I've learned to let it have its way. I have, however, yet to learn to use black confidently as a colour.

Perhaps not being a natural colourist has had its advantages since I've been forced into discoveries by treating all colours alike: it is a version of democracy.

Colour Notes I

An inventory of the names on the labels on all the tubes that so far have been squeezed in the service of this picture would read as majestically as Homer’s epic list of ships. You might from that expect the colour orchestration of the work to be as lavish as in the tone poems of Richard Strauss (with the risk of being as lurid as in those of Respighi) and yet the painting on the wall of my studio seen at any distance is in most lights, a relatively sober affair.

Any detail however, will show the variety of pigments present and the relative purity of their mixtures (e.g. almost no use of black with any of the colours).

As is so often the case in art some larger thing than the actual passages and sections that one is concentrating on will eventually dominate the painting’s character. This overall identity might run counter to any plan and be wholly beyond the artist’s powers of prediction. Similar subverting of intentions is the process after all that gives us for example such oxymoronic emblems as the melancholy clown.

Of all the art forms painting is the most like alchemy. It has much in common with that other unsinister alchemical craft, cookery. Who could predict for example that a mixture of potato leftovers and yesterday's gone-cold greens, when mixed and fried up, would produce that magical and uniquely flavoured dish we call bubble and squeak?

An artist’s manual, with its many recipes for grounds and glazes, its guide to the use of arcane implements and its roster of recommended procedures (e.g. “start lean end fat” meaning don’t use too much oil in the underpainting) is very much like a cookery book. Completely to ignore the precepts of handbooks can lead to disaster as with Leonardo’s self-destructing medium for mural painting or Reynolds’s fatal use of bitumen; yet every chef would understand Picasso’s dictum “If I can’t find the red I use green”. They would also be quick to see the truth in Frank Auerbach’s reply to criticism of the dangerous looking thickness of his paint, “What counts is whether you put it on with love”. Give two cooks the same book and they will come up with different results. As with painting, when garniture serves substance and all is unified, spice against spice, the final dish transcends the recipe.

Here in my own picture, partly through ignorance and partly through the invitation of chance, I find myself producing a thing of unexpected mutability. At differing times of day the colour field presented can range from an aura of mossy green to a slightly baleful purple. In the early morning it may have a blue cast (reminding me of old Westerns shot in Eastmancolor), whereas when seen by electric light alone all the acid fire of reds and yellows awake as if from a sleep to illuminate a quite other kind of battlefield.

Every picture of course is changed in some degree by varying light but none (at least of mine) has ever surprised me with such a range of moods.