Tom Phillips

Can it be another performance so soon after last year at South London Gallery? Yes, as part of the celebrations of the Scratch Orchestra's fiftieth birthday…….The Vocal Constructivists will no doubt have their own take on the piece…….I look forward to seeing what it is. Join me there.

Irma

Monday June 17th 2019

7.30 - 9.30pm

Lumen Church

88 Tavistock Place

London WC1H 9RS

Buy tickets here

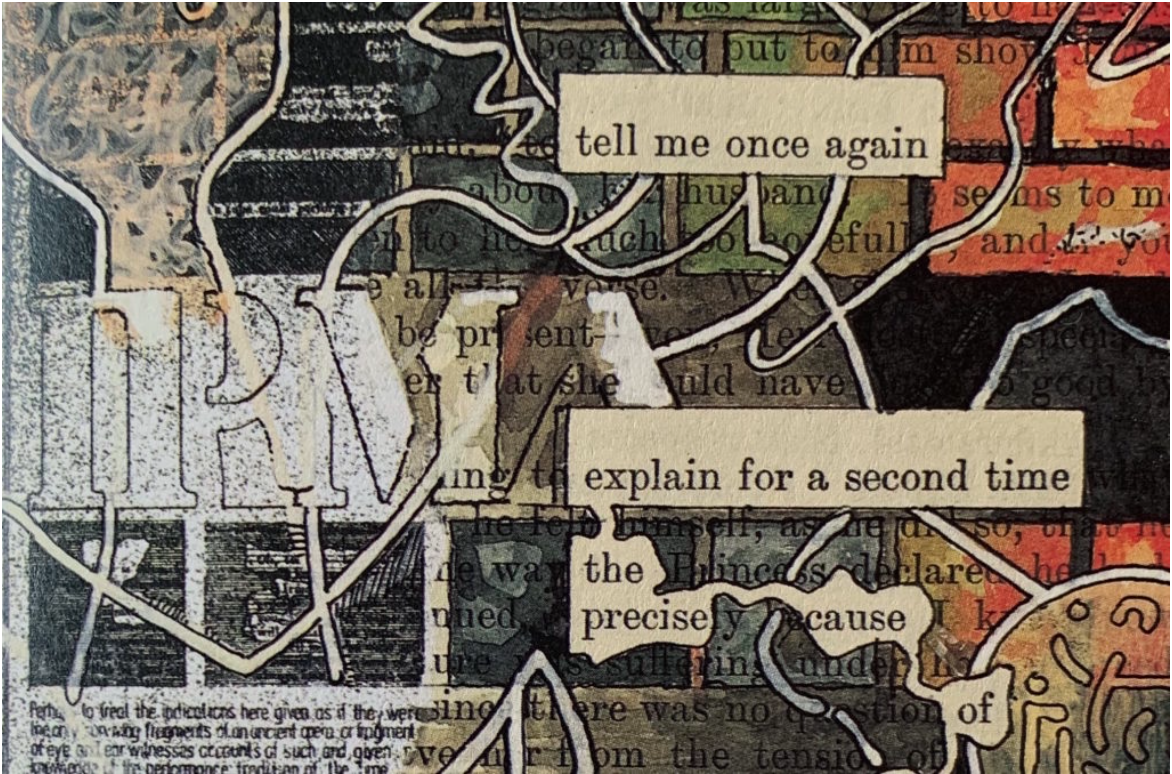

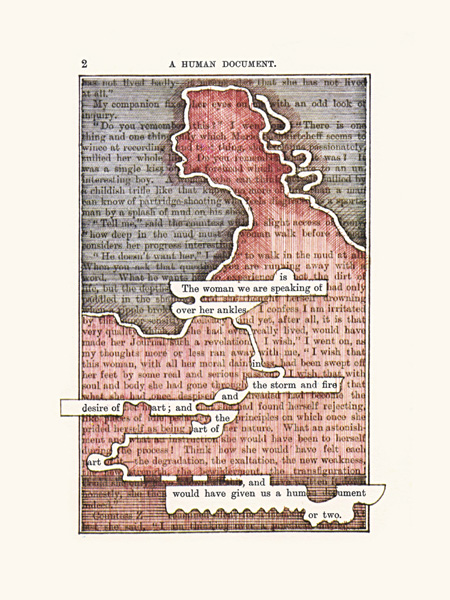

Irma, digital print with silkscreen 2017

To celebrate the year of my eightieth birthday (in May) I am looking forward to two events. Firstly a show at Flowers Gallery called Connected Works which has its opening on the evening of 25th May (6-8pm).

My opera Irma will have the world premiere with two performances directed by Netia Jones at the South London Gallery on September 16th and 17th. This will be the first stageing of the complete version whose score and text I finished last year. I might even be given a small role in it myself…

Meanwhile I am busy reading over a hundred novels as one of the judges of this year’s Man Booker Prize.

Sounds enough to be going on with.

John Cage, 1993, from The Composers series 11 x 12.5cm

Though the programme is called Essential Classics (starting Nov 30th at 10am BBC Radio 3) I have smuggled in some newish music (John Cage, Harrison Birtwistle, Terry Riley, Tarik O’Regan) and have been persuaded by the producer (Chris Barstow) to include some fragments of IRMA. Rob Cowan is the amiable host and interviewer. If you haven’t heard the wonderful Alina Ibragimova playing Bach or the late Michelangeli’s magical Scarlatti tune in to each of the five mornings.

Surprised by the quality Bernard Moxham achieved in the Ulysses/Humument book last year, I saw that self-publishing was now the way to make the sort of book that no commercial publisher could or would take on. Even if you only have one client an edition of one is not only feasible but almost laughably cheap to produce.

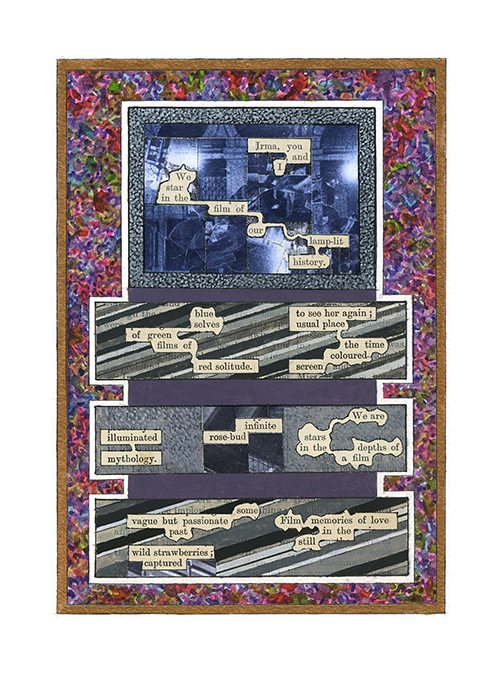

I made a sketch score of an opera, Irma, in 1969 (finishing it as man first landed on the moon). I always had in mind a full score, making it the operatic equivalent of A Humument whose source it shared. Now, forty five years later, as a cottage industry the Talfourd Press presents Irma in full, 120 pages in colour with libretto material and notated score, plus provocative instructions for director, dramaturge, designer and choreographer.

Since writing the first version I have been much involved with the opera stage as both librettist and designer. Irma in its complete form reflects that experience by providing a recipe book for a stage event; with all the ingredients of traditional opera, dance episodes, drinking chorus, mad scene, erotic enactment, and the many variations on love and death. Pipping La Scala to the post will be the forthcoming world premiere directed by Netia Jones. Details to be announced.

Preliminary design for Benjamin Britten coin, watercolour, 2013.

Can a coin sing a song? It can try. Asked by the Royal Mint to design a 50p coin in that oddest of shapes I was thrilled at the prospect yet daunted by the problem of what should appear: the Queen is where she should be and I only have to deal with the obverse.

The idea of illustration soon evaporates as thoughts of Suffolk seas and lone figures on a beach etc. parade their banality. A portrait is not worth considering. Heads is heads and for kings and queens and tails should tell tales of the land over which they reign, and be part of our house of memory. A double headed coin cannot be usefully tossed, and in any case Benjamin Britten’s head lacks the iconic immediacy of, say, that of Einstein.

What I wanted the coin to speak of was music. Thus the stave soon entered the design, in this case the double stave of piano scores since Britten was an eloquent pianist. I found that his name married well with the stave which solved the first problem.

The natural accompaniment with Britten’s passion for poetry as our preeminent composer of opera and song, was some kind of key quotation. I first thought for personal reasons of the Spring Symphony in which fifty years ago with Britten himself conducting, I had sung as a member of the Philharmonia Chorus. The words which however eventually suggested themselves, come from the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings. What better clarion call for a musical anniversary could there be than “Blow, bugle, blow: set the wild echoes flying”.

It occurred to me that a present day function of coinage could be to point people in the direction of a richer experience. If one googles “Blow, bugle, blow etc” one instantly meets a fine poem by Tennyson. If one adds the name Britten one can within a few seconds be listening on You Tube to it being sung by Britten’s life partner Peter Pears at the height of his powers.

A mere 50p coin can in this way become an active rather than a passive instrument.

Aldeburgh, 13th June. During a convivial supper at The Red House after the world premiere of a Harrison Birtwistle song cycle (brilliantly performed by Mark Padmore) Colin Matthews bangs the traditional spoon on the traditional glass. This brings a short silence in which I can speak a little and present to the Britten archive my final drawing for the coin [general murmur of approval from gathered musical luminaries]. I hope it will hang here in the house which Britten shared with Peter Pears. Meanwhile, outdoors on the shingle below they are rehearsing for Grimes on the Beach.

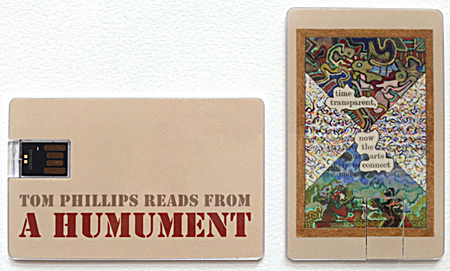

Had the culturati of the late Middle Ages possessed credit cards the piece of illuminated plastic that bears both Humument pictures and their spoken text would have been just the thing to slip into a wallet to while away their tres riches heures.

Nothing more elegant has been made under or in my name than the USB, with which Lucy trumped my original idea of having a video of selected pages, read out by their now croaky maker.

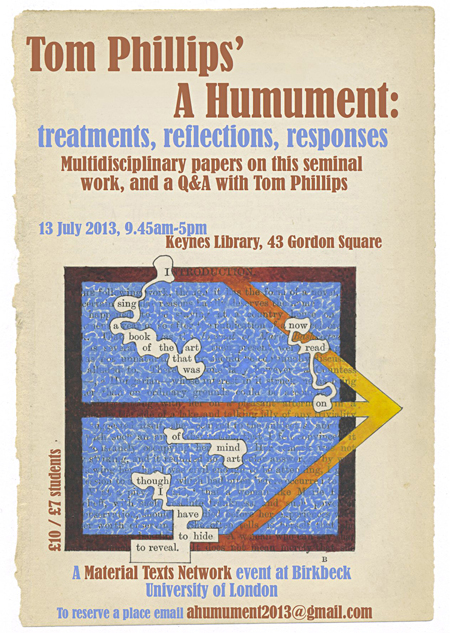

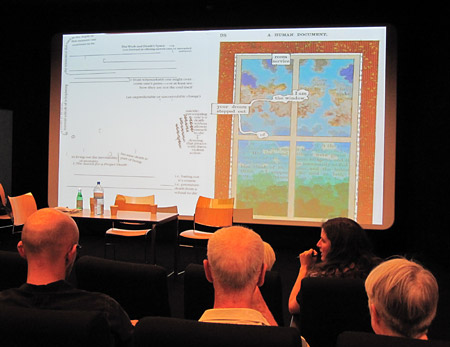

The recording was made many weeks before (at the very table on which the pages were created) with the help of Alice, plus an amazingly small microphone recommended by Tom Service. The furrowed days that followed were spent in the vain attempt to make the operation work on DVD with the deadline of the impending conference on A Humument at London University’s Birkbeck College.

But small is beautiful and a miniature son et lumière event that can slide in next to student ID card or old folks’ bus pass would have seemed unimaginatively futuristic in the kitchen scriptorium where the work was started in 1966.

It arrived on time, bang in the middle of Bloomsbury to be unveiled in the Keynes Library, no less, with the sun streaming in through open windows and people memorially smoking on the balcony. It was there I gave my own talk session to end an invigorating conference, which offered new insights, even to its subject (who was not made to feel the ghost at the feast). Papers were read, to my surprise, not by desiccated specialists in non-linear narrative but by young scholars, and to a largely youthful and cheerfully dressed audience. In the proper scheme of things these were punctuated by occasional updates of the score in the Ashes test. ‘Only connect’ shouted the room as I sat in view of Vanessa Bell’s portrait of E. M. Forster (See blog 28th August 2012) with, on my right, a painting by Duncan Grant who in his old age I once wheeled round a Royal Academy exhibition. Perhaps the USB should have been called, in memory of Virginia Woolf’s chosen brand of tobacco (she rolled her own), ‘My Mixture’.

A Humument conference at Birkbeck College, July 13th 2013.

Tom Phillips reads from A Humument USB drive is available to purchase in our online SHOP.

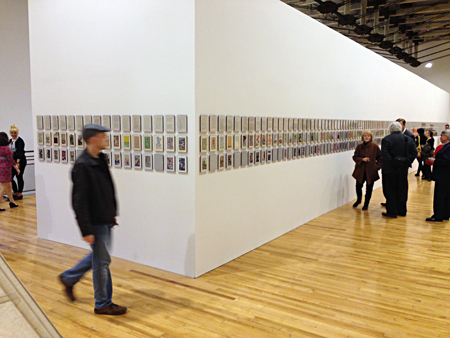

A Humument at MASS MoCA, 2013

Wonders of the world are sometimes to be found in tiny towns. North Adams barely registers on a map of the United States and is little more than an unassuming dot on that of Massachusetts. It houses nonetheless as large a museum of modern art as I have ever seen, almost as long as my street and twice as wide; the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA).

I visited it three of four years ago with my maverick friend and fellow artist Michael Oatman. He suggested that it would be just the right place to show A Humument. The idea grew with the encouragement of curator Denise Markonish. Eventually she suggested some dates for the showing of A Humument in its present entirety, the pages of Mallock’s novel accompanied by my two treatments.

When I arrived at the opening in April I had no idea what the display would actually be like. Coming into the huge hall which houses the show under the title Life’s Work I was stunned with delight at the beauty and simplicity of the installation that Denise Markonish had devised. Instead of my imagined walk around the walls of a room, I faced a huge rectangular block resembling the cast of an inner gallery, round whose outside were more than a thousand frames, like the serried portholes of an ocean liner anchored at an angle within a high hall.

Work energises work, and I have set about filling some of those remaining frames for Version II which, in anticipation, hold blank grey sheets. Half a dozen have already appeared with more to follow as the exhibition heads to its closing in January 2014. One such revised page features Peckham mud combined with that gathered from a nearby river in Massachusetts.

The show has provoked a gratifying amount of interest especially from those who have (often in search of other exhibits) chanced upon it. No reaction has been more wholeheartedly positive, however, than that of the Boston Globe’s chief art critic Samuel Smee.

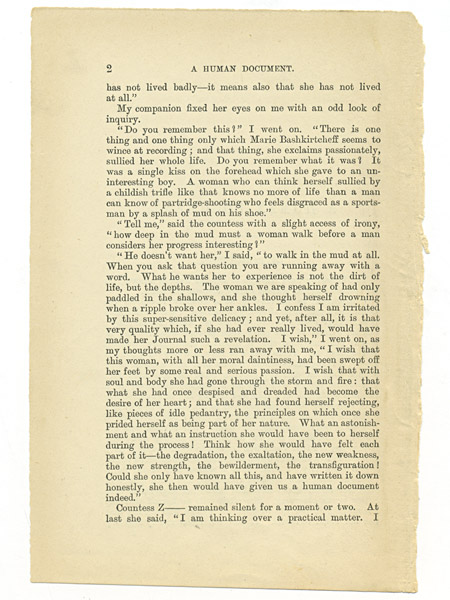

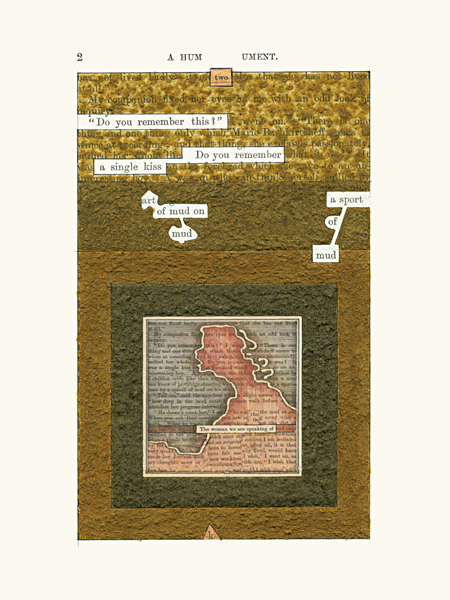

A Human Document, page 2 untreated.

A Humument page 2, first version 1973.

A Humument page 2, second version 2013.

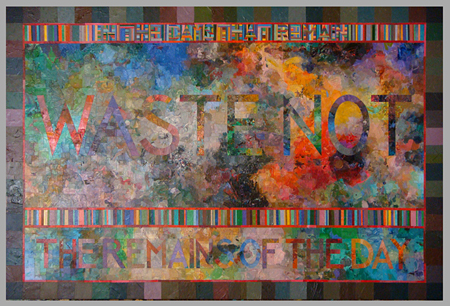

In The Days That Remain, recycled palette collage, 2013

I have already made in blogs above (5.2.13 & 21.1.11) what might be thought the sufficient confession of a serial recycler: yet I must ask the jury to take into consideration one further and extreme instance.

Cutting up the palette mixings for The Remains of the Day and its sequel In The Days That Remain (seen here in its finished state) created its own waste in the form of trimmings; the edges and corners scalpelled off in the process. These become imprisoned in the drying pools of the resin I use in applying the fragments to their panels.

When fully dry these puddled mixtures of resin and paint can themselves be lifted from the saucers that hold them and may in their turn be applied to another surface.

Lurking unloved in a corner of the studio I found the ideal partner in the form of an unfinished painting, a failed drip/stripe work of the seventies. Each day’s waste now finds its way onto this now recycled canvas, one kind of aleatory accident making an almost musical counterpoint to the other; a staccato texture above the lyrical progression. So far (see below) it seems to be working. When it is done I shall perhaps be able to rest my case.

The state of play in my studio and those pseudo studios in Talfourd Road that occasionally masquerade as bedrooms, kitchens and bathrooms is, as usual, complicated. The unifying feature I begin to realise is some form of recycling. Ever since I picked up a Victorian novel (in 1966) and borrowed a postcard of Burnham On Sea (from Nancy Davies in 1968) to paint from, everything I do has seemed to involve the transmutation of source material or, as in the case of mud and hair etc., of material sources.

I write this in the kitchen which, apart from making coffee or the odd microwaved meal, is used for postcard storage and sorting and the preparation of books. With the exception of two or three completed at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, every page of both versions of A Humument has been done in a kitchen. Around me in shoeboxes and albums is my collection of 50,000 or so vintage photo postcards of people. Slowly these are decanted into the little volumes for the Bodleian. The next categories to appear are Walls and Sport and, with Alice, I am starting to sort out the selection for Dogs (or rather, people with dogs).

In the eighties I started (and for some reason abandoned) the project of making a diary of a composite day, minute by minute by minute for 24 hours, the minutes coming from different days in different years. Perhaps urged on by my admiration for Christian Marclay’s film masterpiece The Clock, I have taken up the task again. By now the minutes can be over fifty years apart. Currently the earliest entry is for 1957 and the most recent comes of course from 2013. This book is not, like Ivan Denisovitch, A Day in the Life of but rather A Life in the Day of Myself. Of the 1440 possible entries I have finished about two thirds, gleaned both from that first attempt and from other diaries and pindownable moments from various notes. Each page features ten minutes, one of which should provoke an illustration of some mentioned work or place or person.

In another room my central activity for the past months is a painting carrying on from The Remains of the Day (see blog January 2011) shown here in painful progress. It is very near completion under a title which reminds me (as if I needed reminding) of the ever nearer approach of time's winged chariot; In the Days that Remain. More of this when it is finished with that necessary coat of varnish that will hold the whole precarious thing together.

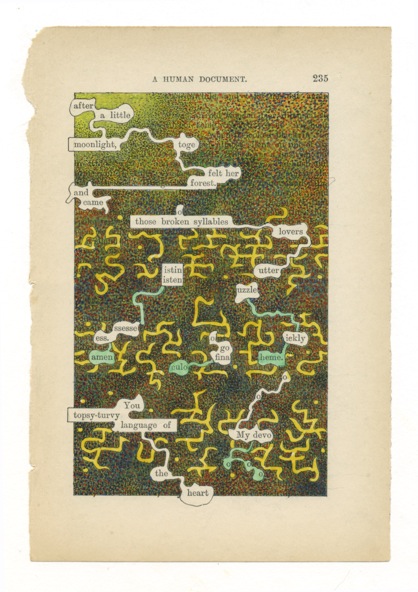

p.235 A Humument 2012

In 1975 I recorded, on one of the two B sides of a vinyl LP (Words & Music, produced by Hansjorg Mayer) some of the pages of the first version of A Humument. I spoke them into a huge hairy ball of a microphone amidst a tangle of wires and cables.

A sudden wave of critical attention (noted here) has tended to concentrate more often on the words rather than the images of the book. I was particularly touched by the appearance of a page on the cover of the Poetry Review announcing a fine article by Chris McCabe. Time, I thought, for Jolson to sing again especially as Tom Service had just shown me the recording device he uses for his BBC interviews, a cordless microphone no bigger than a Mars bar.

Here for a start, in full son et lumière, is a page I've just finished. More to come and, to quote the quote from Dickens that was the original title of The Waste Land, I do the police in different voices.