Henri Matisse : The Cut-Outs

This article first appeared in The TLS, 23 May 2014

Matisse never forgot the excited gleam that came into the aged Renoir’s eye as, with the knotted claw of his arthritic hand padded, a paintbrush was squeezed into the tight gap between two fingers. It was the moment when he would overcome torture, transcend his skeletal frailty and once more escape into work. “I have never seen a man so happy, and I promised myself that, when my time came I would not be a coward either”, said Matisse, who became a frequent visitor to the revered master after a first shy and formal encounter in 1917. He often talked with him through the evening as the fading light gave notice of the agonies of a sleepless night ahead. “The pain passes, Matisse, but the beauty remains”, the old painter once said as he looked forward to some still distant morning session at the easel. Matisse had in fact contributed to the delight of that anticipation by finding him a new model, one of those pneumatic and roseate girls who, replacing each other in succession throughout Renoir’s career, managed never to grow old.

Less than a quarter of a century later Matisse himself faced as brutal an ordeal in the long aftermath of massive intestinal surgery in 1941 with the attendant encumbrances and complications that would quickly make him an invalid. Asthma and heart problems also punished him: even his eyes and teeth came under attack. A series of reprieves (negotiated in Mephistophelian fashion between his willpower and the skill of his doctors) allowed him to last out, with rationed months so that this or that task or project might be finished, until 1954. The fine, still stubborn head of the bedridden artist in his last days was the subject of six touchingly drawn studies by his colleague Giacometti.

These are grim matters with which to start an account of what may be the most uplifting show ever to be put on in London, yet they are an essential heroic background to its triumph. Quite early on in the preface to a majestic sequence of rooms a fragment of film shows Matisse in his wheelchair cutting paper with scissors: not of course the fiddly scissors of the silhouette-maker but something more akin to a tailor’s shears. The paper is being manipulated by an assistant whose hands move in agreement with, almost anticipating, the swift curves of the slicing blades. Matisse often associated this process of “sculpting in colour” with flying, though another action that comes to mind is a favourite pursuit of his younger years, swimming, especially as evoked by his own descriptions of plunging into the volcanic lagoons under what he referred to as the “golden goblet” of the Tahitian sky.

Matisse habitually maintained a severe photographic presence. The mere sight of a camera lens induced a stiffness of bearing and formal frown that he thought appropriate to a serious artist. Here and there, however, in such film clips, as yet another algae-like shape loops its way to the floor, one can just catch a hint of that long remembered gleam of delight in Renoir’s eye. Meanwhile the blades of the scissors do not snap but glide. The deceptive ease of a virtuoso recalls another Matisse, the violinist of professional ability, who used to practise four hours a day and who once in a favourite Moroccan café picked up a violin and entertained its habitués with his improvisations.

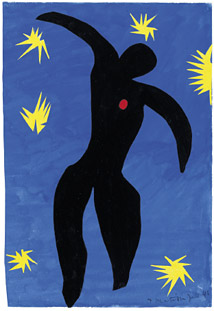

Any show that covers such a substantial epoch in a great artist’s life and proceeds in chronological fashion will at some juncture feature (to return to Matisse’s own image of flying) the moment of take-off when the runway starts to fall behind as the engine’s power is sensed. The analogy becomes ever more appropriate in this context since the show gathers impetus and scope as it heads for broader skies. This point, with the artistic engine revving, is a room entirely devoted to the set of twenty works that became one of the most famous artist’s books of the century, Jazz.

It is a work that has special significance for me since I was able as a student in Paris in 1955 to study a copy of it at leisure. This, however, left me unprepared over fifty years later to see the whole set of original maquettes and the published book together. I confess to having thought the book supremely well produced at the time, but now can not look at it without the sharp awareness of the gap in quality between the intense and vibrant originals and the muted versions in the published volume. Tériade, Matisse’s publisher, thought, in all sincerity, he had found the right method for transposing these concentrated masterpieces by using the parallel painstaking pochoir/stencil method. The results however, in direct proximity to the originals seem to lie dead on the page. Two aspects of difference are compounded. First, the colours afforded by the printing inks are no match for the artist’s painted paper. Gouache paints are the grown up version of what at school one might have known as powder paints. They are full bodied opaque versions of watercolour. They breathe the light and hold its strength. The second missing factor is physicality. The gouaches are unique and real and their material existence, however slender the paper and however closely they are attached to their support, makes them a kind of relief object. Each of the pictures in the book is complemented on the facing page by Matisse’s text, free flowing in its thought as well as in its form. Via the artist’s large looping handwriting the words rest on the paper as they should.

Matisse considered the book as produced a failure. But he was good at lessons to be learned from disappointment. The artist had been shown that with the cut colour he was making things, not merely reproducible designs. The struggle from now on, technically,would be to retain the substance of what he made with his colour cutting scissors: that lesson mastered gives the subsequent work its unique wings.

The title of the volume, Jazz, was about the liveliest word in circulation in Paris in that period, which was where American music had found its second home. Matisse enjoyed jazz and would play records of it as well as dance and ballet music to his assistants. As a word “jazz” is not only a calligrapher’s delight but also presented a warning to any would be imitators of Matisse's new methods. This was best summed up in Duke Ellington’s little masterpiece, recorded by his band (complete with an opening riff on the violin) in 1943, the year of Matisse’s first images for the project: “It don’t mean a thing / If it ain’t got that swing”.

Like uncaged birds the various types of element so compressed in the Jazz images began to free themselves, initially one by one and then in flocks, to land on the walls that surrounded Matisse in his studio homes. Eventually they would group and regroup themselves into compositions, disciplined yet unconfined by the boundaries of canvas or frame. Matisse abandoned painting in favour of this aerated and infinitely flexible system that with the help of assistants could be masterminded from wheelchair or bed. Matisse, always the one in charge of the scissors, was composer, conductor and orchestrator, making adjustments and revisions in the course of arduous rehearsals. All his observations and memories of plant and marine life came into play, not to speak of his long study of the female form.

Minor decorative supporting images, pomegranates, stars etc, were mostly grouped like pawns in an endless series of variations around major thematic pieces. When they were too powerful to be contained, these pieces pieces sometimes sought their autonomy. Such is the case with “BlueNude2” which at one time was inserted into the large composition “The Parakeet and the Mermaid”. In photographs of that installation at an interim stage the large figure can readily be seen as far too overbearing a motif.

Eventually, there were four of these life size cut-outs. Here they are given a room to themselves, accompanied by a telling group of Matisse’s sculptures of the subject. This provides one of the most informative delights of the exhibition, an opportunity for the visitor simultaneously to appreciate both how well drawn the small sculptures are and how well sculpted the energetic blue drawings. The first of the nudes was achieved with great difficulty over two weeks. Many of the prepared blue-painted sheets were used up as large changes were made, supplemented by numerous tiny additions, all now witnessed by a forest of pinholes. Paule Caen-Martin, the assistant who worked on it, described the exhaustion she felt at the end of those long days.

The other three images, however, were each cut in one brief session. One of them (number two in the series) has justly become the trademark of Matisse’s cut-outs, soon being reproduced worldwide in every medium and at every size from postage stamp to poster (as well as providing an obvious choice for the cover of the current exhibition’s catalogue). It is a feat of composition, drawing and anatomical empathy whose popularity suggests that a larger public than is normally supposed can sort out and applaud the best of the best.

The language of its marks where drawing cuts through form using the white negative of the paper support to stand for both the darkest area of implied shadow or the spaces in between limbs (or both ambiguously, as in the gap between the torso and left arm) is stunningly inventive. Curiously enough, this manner of breaking down the elements of a figure or face with blank space replacing both the outlines and shading of conventional draughtsmanship was prefigured in the coins and seals of the ancient world. This was demonstrated in André Malraux’s Les Voix du Silence, a book that advertised itself as “a museum without walls” when it appeared in 1951, featuring exotic and classical Western art side by side, including huge enlargements of tiny masterpieces such as the silver and gold coins of Alexander the Great.

The room of the Blue Nudes demonstrates the brilliant curatorship of the exhibition as a whole under the direction of Nicholas Cullinan of the Metropolitan Museum with a team including Flavia Frigeri and the Tate’s own director Nicholas Serota, whose personal enthusiasm for the late work of Henri Matisse knows no bounds. Such a comprehensive group of cut-outs will probably never be seen again. The only absent work whichwould have added both grandeur and gravity to the final rooms is “The Sorrows of the King” (1952) the last and most atmospheric of the large scale stand-alone pieces in which music and dance, two of Matisse’s lifelong themes are brought together.

Luckily, one of the Tate’s own most popular acquisitions, “The Snail”, together with its companion piece “Memory of Oceania”, carry some of this weight. They were among the works which initially formed part of a larger ensemble (which eventually became “Large Decoration with Masks”) but like the “Blue Nude No. 2” were given solo existences. Nonetheless they look happily reunited after sixty years. “The Snail” itself started life as a series of studies made by the artist of a small snail held and turned between two fingers yet ended up as a daring combination of gigantic pieces of coloured paper making a lyrical abstraction, a slow spiral of a dance which Matisse initially called “Chromatic Composition”. This title he soon came to regret since it seemed to suggest he had become an “abstract” artist.

As the number of walls covered and the number of assistants employed increased, these developments in Matisse’s working methods led to the general adoption of the word “factory”. (Andy Warhol’s later use of the same word is not without intriguing artistic parallels). For a period, there were in effect two Matisse factories once the long adventure of the Chapel of the Rosary at Vence gained its own momentum. Few artists even in their prime have juggled with so many large scale projects in so short a time. The chapel was consecrated in 1951. Matisse, after four year designing it in every detail, windows, walls, even the bronze cross on the roof and the vestments to be worn by the clergy, was too frail to attend. Cut up maquettes for the stained glass as well as preparatory drawings for the murals long dominated the studio at Vence. The designs for the chasubles were much admired by Picasso who nonetheless disapproved strongly of Matisse’s using so much of his last energies on a house of religion.

Their ancient and once fierce rivalry had by now mellowed into a guarded but supportive friendship. Picasso made regular visits together with the young Françoise Gilot. Matisse could not help suspecting that Picasso was keen to take in and learn from the strange innovatory work of his friend whom he was in the habit of calling “the magician”. (Matisse in return jokingly referred to Picasso as “the boss”). Picasso’s comment on the final version of the last and biggest of the older artist’s work, the “Large Decoration with Masks” – “Only Matisse could have done anything like that” – had a characteristic though not unfriendly ironic touch as if to say “Only Matisse could get away with doing a thing like that”.

Matisse himself also had a much younger companion in Lydia Delectorskaya who now, having been his model, muse and pioneer assistant in the making and manipulation of cut outs became at the end of the war his factory manager, factotum and principal carer as well. she had in fact joined theMatisse household in 1932 at the brink of its domestic collapse. However close her relationship with the artist grew in terms of interdependence, there was no romantic or sexual element to it. He called her Madame Lydia and she addressed him as Monsieur Matisse. Nevertheless, Lydia was the catalyst in the final breakdown of the Matisse marriage. The tale of the multiply dysfunctional House of Matisse is long and bitter. It is documented with commendable sensitivity in Hilary Spurling’s definitive biography (2005).

It was Lydia who largely recruited the assistants, always glamorous girls in their twenties. In their natty working uniform of pastel blue dungarees they looked to the outside world suspiciously like a harem. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Though Matisse was always generous and saw to it that the girls were well paid and, in those lean times, well fed, he was an employer as demanding of them as he was of himself. Sundays were not days off and hours were long. Much of the work was mechanical, such as the exacting task of covering innumerable sheets of paper with gouache of the right density. Dismissals seem to have been frequent. Even Paule Caen-Martin who had proved so adept in working on the Blue Nudes was sacked without ceremony because she kept late nights and wanted time off when she was tired.

However, that second pair of hands we see on film at the beginning of the show are probably Lydia’s, whose devotion to the work did not end with Matisse’s death. Her services were much called on for the completion and conservation of the cut-outs. She was also, until her own old age (she died in 1998) a valuable source for commentators on the artist’s life and work. Another of the ancillary roles she had taken upon herself was as a part-time photographer of studio activity. Some of her photographs enrich the exhibition’s exemplary catalogue. This in addition to its brief essays (mercifully free of art speak) features useful coverage of Matisse’s earlier experiments with cut and coloured paper which date from studies for the Barnes mural “The Dance” at the beginning of the1930s and, even before that, to ballet designs for Stravinsky’s Le Chant du Rossignol commissioned by that cultural Svengali Serge Diaghilev. The whole volume is a lavishly illustrated companion to the show and can of course be found in the merchandise room as you exit. Here, if you suppose (as many did and a few still do) that Matisse had found an easy, almost childish, way of making spectacular art, you can also buy a pair of scissors.